Magical Mystery Tour

For many Jews for whom Judaism has failed to bring inner peace and an answer to Mideast and other worldly chaos, Tibetan Buddhism beckons

Tibor Krausz

The Jerusalem Report, March 12, 2001

Dharamsala, India

Floating leisurely in the cotton-dabbed blue air, the pine-clad Himalayas lend an elevated backdrop to the hive of spirituality below. Bald, burgundy-robed monks stroll the dusty streets, fingering their dried-seed rosary beads, as melodic chants mingle with the chorus of cicadas. Worshippers in lavishly embroidered dresses earn merit by twirling mantra wheels. Everywhere, inscribed prayer flags flutter invocations to the winds. The setting befits the spiritual epicenter of Tibetan Buddhism and earthly seat of its reincarnated Buddha, His Holiness the Dalai Lama.

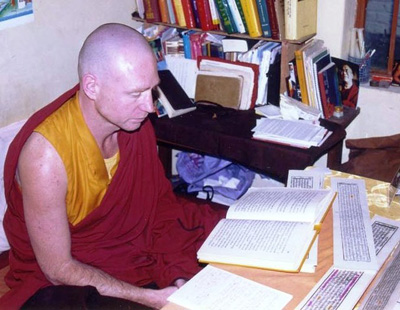

Buried behind ancient Buddhist manuscripts written in intricate Tibetan script sits Venerable Tenzin Josh in the lotus position of monks, head shaven and wrapped in maroon robes. His simple cell with its wooden desk and mattress in Dharamsala's Buddhist School of Dialectics belies his previous incarnation as Steven Gluck, a scion of well-off Jews in London.

Down a narrow winding road from his monastery, Ruth Sonam sits at the feet of Lama Sonam Rinchen at the ornate Tibetan Library. Formerly Ruth Berliner, the Belfast-born daughter of Holocaust survivors, Sonam is rendering the Buddhist master’s Tibetan parables into English for the roomful of foreigners gathered for an hour of oriental wisdom.

Uphill, through the pinewoods to the village of Dharamkot, Itamar Sofer, an ascetic young Israeli, manages the Vipassana meditation retreat’s daily workings — when he isn’t immersed in silent meditation, like other 70residents.

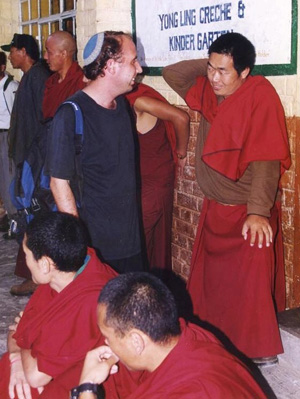

Jews crop up prodigally around Dharamsala in meditation and yoga courses, Reiki workshops, Tai Chi sessions, and Buddhist lectures. After searching in vain for meaning in Judaism, or not even bothering to search in it at all, many Jews and Israelis come to seek answers in the great spiritual bazaar of India. Afro-haired Hindu swami Sai Baba in Shirdi draws many with his religious universalism, as does the commune of the late guru Osho, in Pune.

But most Jewish seekers make pilgrimage to Dharamsala. Buddhism is hot, and Tibetan Tantric Buddhism is even hotter: it’s esoteric and mystical, exotic and colorful. And it’s different. Where Judaism may seem parochial and divisive, Buddhism appears universal and all-embracing. It preaches love and teaches that peace comes from inside the self, not the outside world of chaos — a ready sell with Israelis.

Avi Strul, a 28-year-old software designer from Tel Aviv who sports a gaudy knitted hat and a scarlet wool blanket wrapped around his shoulders, made the grueling 14-hour bus ride from Delhi through the scenic Punjab state to Dharamsala last October, to see for himself the source of his Israeli friends’ endless stories. Strul signed up for an eight-day meditation course in the local Tushita retreat, where participants meditate long hours in a monastic environment. Half of his 58-strong class were fellow Israelis. “They told me,” he says, “you can reach enlightenment (the aim of all Buddhists) in one lifetime. Do I believe in Buddhism? I don’t know, but I am going to check it out.”

Kalanit Cohen, 38, from Netanya, also wants to explore. A mother of three with bleached short hair, a turquoise nose-stud, and crystal-encrusted fingers, she grew up in a strictly Orthodox family, studied in a yeshivah, and served in a religious army unit. Now, having left her family for three months, she is staying in Dharamsala, hoping to “find my true spiritual self.” “I am blocked up.“ she tells me over hot Indian mint tea. “I want to open my chakras, especially my third eye, to see beyond the trivialities of life.” Chakras, in Hindu-Buddhist thought, are energy centers in the body, with the third-eye chakra, marked by a blob of red paint between the eyebrows, designating spirituality. “If I could find myself in Mea Shearim, I’d go there,” Cohen says. “Instead, I came here.”

* * *

While many Jews are searching for an alternative self, others have already found it. Steven Gluck found his in Tenzin Josh. Gluck, 36, grew up in a Reform Jewish home in London, where he attended Sunday school and wore a kippah for holidays in the local Reform synagogue. Yet he found more meaning in revelry than religion, becoming a self-described “hooligan.” “My bar mitzvah sort of touched me,” he recalls, in the short break between intensive classes of philosophy at the Buddhist School of Dialectics, where he is gearing up for his Geshe exams, the Tibetan Gelug-pa (“Yellow Hat”) order’s highest degree. “But even so, I got very drunk.”

And he barely stayed sober thereafter. The hooligan turned punk: Gluck sprouted a rainbow-colored mohawk and a faceful of piercings. Drugs and police arrests came naturally.

Contrast that with the serene, self-effacing monk who wears a Tibetan rosary of mala beads around his wrist and gulps down his spinach-dish lunch, the sooner to return to his studies of sacred Buddhist sutras. But what seems a jump-cut from punk to monk was to him simply a crossover. “It’s not a big leap,” Gluck says. “Whether a punk nihilist or a Buddhist hermit, you just don’t see a point in life and want to find a way out.”

And Judaism wasn’t an option. “Buddhism holds that life is suffering but the Buddha’s teachings show a clear way out of it (through Enlightenment). The Jewish idea, on the other hand, is just try to adapt.”

Still, his conversion didn’t come overnight. Before Buddhism, Gluck, who studied law and psychology at university, experimented with New Age creeds, astrology and other fads of the alternative spiritual scene. One day he saw a picture of a Tibetan monk in contemplation. “That’s the way to live!” he thought. He bought a one-way ticket to India, and joined a silent retreat in Dharamsala, meditating 14 hours a day for the next six months. After a year-long stint as a novice in a Tibetan monastery in Kathmandu, Nepal, Steven Gluck became Venerable Tenzin Josh. He was ordained by the Dalai Lama in Dharamsala.

That was nine years ago, and he has kept an austere regimen since. His day lasts from 5 a.m. until midnight. He prays and meditates, meditates and prays, invoking the names of great lamas and murmuring the Tibetan mantra of compassion “Om Mani Padme Hum.” He memorizes sacred sutras such as the Bhagavati Prajnaparamita (The Perfection of Wisdom), and debates the finer points of Buddhist philosophy with his fellow monks in noisy, animated sessions, driving points home with flourishes and loud claps. And of course, he tries to keep the monk’s 253 vows, with several precepts eerily resembling Shabbat prohibitions (he dresses modestly, touches no money, and doesn’t cook, for example), in addition to special rules like not eating after noon and not sharing private space with women. “It’s not much different from being an Orthodox Jew,” Tenzin Josh explains.

He admires Orthodox Jews for their dedication to learning; but his feelings aren’t necessarily reciprocated. During a lecture tour on Buddhism in Israel in 1998, Tenzin Josh, garbed in his maroon robes, visited the Western Wall in Jerusalem to reconnect, if only momentarily, with his abandoned religion. A group of Orthodox worshippers surrounded him, he recalls, to try and persuade him to return to Judaism. Finally, they gave up, advising the Buddhist monk: “Find yourself a better religion!”

If he isn’t a Torah scholar, his dedication is hardly in question. “Josh is more devoted than our own Tibetan students,” says his teacher Gen Gyatso, a polite Tibetan with large thick glasses and a ready smile that reveals a glinting gold tooth. “He’s still a Jew, but his religion has changed. To become a Buddhist, you don’t change your identity; you change your way of thinking.” (Buddhists consider their faith more a philosophy than a religion and frown on conversion.)

Tenzin Josh’s family holds no beef about his metamorphosis, either. “My mother’s quite happy I’m doing this,” he says. “Even though she’d rather I was back in England and married to a nice girl.” She may get part of her wish. The Dalai Lama has asked Tenzin Josh to take his Buddhism back to England and open a monastery.

* * *

With Christianity and Islam usually considered taboo, Buddhism has long fascinated Jews. American poet Allen Ginsberg found his Muse in it, and David Ben-Gurion practiced Buddhist meditation. Numerous Jews have donned robes as monks and nuns, and astonishingly a third of all Western Buddhist leaders come from Jewish roots, according to Rodger Kamanetz, author of “The Jew in the Lotus.” They include former monk Jack Kornfield, founder of the Insight Meditation Society in the U.S., and the American Zen Buddhist roshi (elder master) Bernie Glassman.

In Dharamsala, too, Jews play a prominent role in preaching the virtues of the Dharma (Buddhist Way). Take Ruth Sonam. She sits cross-legged on a pancake-flat cushion at the feet of her master, Lama Sonam Rinchen, in a packed room at the Tibetan Library and leads listeners in the puja, the recitation of incantations and mantras, before the daily lecture on Buddhism. Then, as the abbot of a local monastery, whom she addresses as “Gen Rinpoche” (Precious Teacher), expands on Buddhist wisdom, she translates his melodic Tibetan into English for the mostly foreign audience (many from Israel) under the benevolent gaze of a smiling Dalai Lama portrait.

Sonam, 57, who changed her name from Berliner after she married (but soon divorced) a Tibetan man in Dharamsala in 1974, has been at Lama Sonam Rinchen’s side for over 25 years as his associate and translator. Like Steven Gluck, the Oxford-educated daughter of German Jewish refugees in Belfast found her Judaism alien and alienating. Her parents were liberal Jews in the small but strictly Orthodox community of Northern Irish Jewry. “I always had a spiritual desire, but Judaism wasn’t accessible to me,” she says. “I’d go to the local Orthodox rabbi’s for Shabbat, but I understood little Hebrew and didn’t know the answers to his questions (about the Torah).”

Instead, she found answers in Buddhism. She embarked on a pilgrimage of the Buddha’s holy places in India and was among the first Westerners to begin studies in 1971 in the just-opened Tibetan Library in Dharamsala, then still a shepherd village. She mastered Tibetan and made the town her new home. And she became the protégé of Lama Sonam Rinchen. It’s been like a spiritual marriage — she’s never left him for more than a few days. They even bicker like married people. During the lecture at the library, she will chide the lama when he gets carried away (“Just to backtrack a little bit!” she admonishes him), or spar with him about nuances of philosophy in flowing Tibetan, shaking her head in disbelief at his explanations to the amusement of Tibetan listeners.

Over the years, she’s become an authority on Buddhism in her own right. She has co-authored five studies with the lama on Buddhist philosophy (all published in English in the U.S.), and is working on their sixth book, about the ways of reaching Enlightenment for the sake of all sentient beings.

But she hasn’t reneged on her roots. “I still consider myself a Jew,” says Sonam. “It’s so Jewish, you see, to always talk about suffering, as Buddhists do.” At the request of Israeli friends, Sonam recites Buddhist prayers regularly with the lama for peace in Israel.

* * *

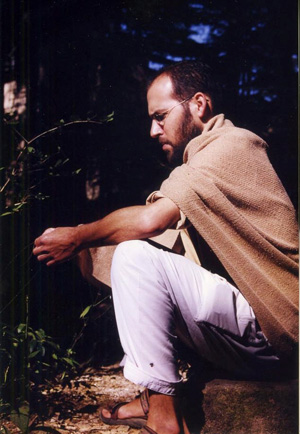

Many Israelis escape to India in search of just that — peace. Itamar Sofer, 32, commanded a tank battalion between 1986 and 1988, at the height of the first Palestinian intifada in the hotspots of Gaza. His service exacted a terrible toll on him. “War brutalizes you,” says Sofer, a lean ascetic man from Kibbutz Bahan, near Netanya, who might pass for a rabbi with his thinning hair, neat beard, and glasses if not for his penchant for sitting in the folded-kneed lotus position. Alcohol and hashish helped him cope for a while, but eventually he gave in to despair. “What hope is there,” he summarizes, “when your whole life is one ceaseless fight for personal and national survival? I just wanted to run away and find some space for myself.”

He ran as far as India. He trekked to Rishikesh (a yogi stronghold in northern India), latched onto flowing-locked gurus, and followed them into “deserts and jungles” for intensive yoga sessions. In 1995, he hitched a ride to Dharamsala, where he became a hermit, renting a shack in the neighboring pinewoods and losing himself in contemplation. He emerged back to civilization only to join the Vipassana meditation retreat in the village of Dharamkot, uphill from Dharamsala. At Vipassana practitioners expect to purify themselves mentally and spiritually and to “penetrate the mystery of reality.” They abide by the Five Precepts of Buddhism (abstinence from killing any living beings, theft, sex, falsehoods, and intoxicants) and observe Noble Silence by refraining from any communication with others (including eye-contact and gestures) for the 10-day duration of a beginner’s course.

Advanced students like Sofer don’t eat after midday, live in seclusion without any form of entertainment, and sleep on blankets laid on the bare floor. (“I’m a monk without the robes,” he says.) The most senior student, Sofer now doubles as the center’s manager in return for board and lodging. “Buddhism has shown me a way to liberate myself from constant worries and helped me master my emotions,” he says.

And it helped him find his peace at last. Last year, Sofer revisited the scenes of his wars in Gaza, accompanied by a Jewish-born American Buddhist nun. In the Jebaliah refugee camp, he bonded tearfully with his former enemies, beseeching Palestinians for their forgiveness. “Before, I was chasing (rock-throwing) children with guns; now, I was hugging them,” Sofer recalls. “Israelis or Palestinians, we both just want to be happy and get out of suffering.”

His transformation is hardly unique; at least half of all participants at Vipassana, Sofer says, are Israelis — many just after their army service and several wearing yarmulkas for meditation. “I’ve met thousands of Israelis but not one who hasn’t been changed in Dharamsala,” he insists. “They all want peace and here they realize they can’t make peace with Arabs until they find peace in themselves.”

Gilah Panfil has arrived at the same conclusion. A petite 48-year-old woman from Jerusalem, she gave up her job as a commercial graphic designer in 1997 and relocated to Dharamsala to learn about Tibetan Buddhism. She sits in on the daily philosophy classes at the library and attends the Dalai Lama’s public lectures. Last year, he requested the Dalai’s permission to translate his book “The Way to Freedom“ from English into Hebrew. The book, the Dalai Lama’s first translation into the Jewish vernacular, hit store shelves in Israel last November, with a special foreword by the lama himself to the Israeli reader, on occasion of his visit to the country. “In Israel, with all the violence, we feel justified to be angry and vengeful,” Panfil says. “But anger and violence lead only to yet more anger and violence. His Holiness can teach us how to break this terrible cycle through compassion.”

Panfil is now translating “Awakening the Mind, Lightening the Heart” by the eminent Buddhist teacher, to be published in Israel next year. “Our rich traditions of compassion in Judaism have been politicized beyond recognition in Israel, and ironically many of us now have to turn to Buddhism for answers,” she says.

Other Israelis, too, have taken Buddhism home from Dharamsala. Meditation retreats are mushrooming around Israel — there’s now a Vipassana center in the Negev — and Buddhist philosophy courses are also in vogue.

* * *

Alienated, liberal, non-observant — it fits the profile of most Jewish seekers in Dharamsala, but hardly all. There are also Orthodox Jews who try to broaden their religious horizons through Buddhism. Eitan Turkel wears a crocheted kippah, keeps strictly kosher, observes Shabbat, puts on tefillin for his daily prayers — and meditates at the Vipassana retreat. A New York-born yeshivah student from Ra’ananah, whose father is a rabbi, Turkel set up camp in Dharamsala last August in order, he says, to “see how I can grow spiritually.” “One day I asked myself,” Turkel explains, “Why do I believe in Judaism? Because it’s the only religion I’ve known. So I decided to study other faiths.”

In his Modern Orthodox yeshivah in Jerusalem, students experimented with Jewish meditation and Kabbalistic mysticism, and — guided by a rabbi who had visited India — compared it with Buddhist techniques. It let the genie out of the bottle. “Half of my yeshivah is in India now,” Turkel says.

During meditation sessions at Vipassana, where participants are barred from practicing religious rites, Turkel would recite his prayers in silence and put on tefillin secretly, in the privacy of his room. “But if it really stretched things, I’d let my observance slip,” he says. “I felt that right then I’d get more out of Vipassana.”

This past Yom Kippur, he trotted down the hill from Dharamkot to listen to the Dalai Lama in a public audience at his monastery in Dharamsala. Then he legged it back up to the Jewish service at the local Chabad outpost. “If I become convinced of Buddhism, I hope I’ll have the strength to change my religion,” Turkel says, mixing Jewish terminology in his conversation with Buddhist terms like “karma.” “But I feel I can take a lot from Buddhism and use it in my Judaism without becoming a Buddhist.”

In a bid to bring the two faiths closer together, he volunteered to teach Buddhist monks about Judaism. At a class in a Tibetan school, before which he steps out on the balcony to daven at sunset, silhouetted against shadowy mountain ranges, he takes the prayer “Shma Yisrael” and compares it with Buddhist thought. Judaism centers itself on the love of God; Buddhism considers God worship meaningless. In Judaism, the family lies at the heart of human relationships; in Buddhism, the ideal is to become a celibate monk.

But some fundamentals do match. “Guard my tongue from evil and my lips from speaking guile,” Turkel recites from “Hear, O Israel” — and his attentive listeners clamor in amazement: it’s just like the Buddhist precept of right speech. “It’s even the same wording the Buddha would use!” exclaims Lobsang, a young monk from Tibet.

It’s because of such overlaps that some Jews come to India in search of Buddhism — and instead find Judaism.

* * *

With his black fedora, mutton chops-like beard and all-black attire, the Lubavitcher hasid appears as far a cry from a burgundy-robed Buddhist monk as it can get. Yet Zohar David, the 30-year-old Chabad emissary in Dharamkot, came very close once to becoming a Buddha devotee himself.

Just out of the army in 1991, David, then a secular Israeli from Yemenite stock, landed in India, searching for meaning. His quest took him to a Tibetan monastery in Nepal, and soon, he says, he was well on his way to taking the novice monk’s vow: he fasted, meditated and studied vigorously. Then a fellow Israeli gave him a copy of the Jewish mystical book, the Zohar, and it set him thinking. “The Buddhists talk about reincarnation and we talk about reincarnation,” he says in the garden he shares with Reiki practitioners. “But then, I wondered, there must be a reason why I was born a Jew.” The Kabbalah explains that, before reincarnation, souls choose the best bodily vessels for spiritual growth and so souls become Jewish for a purpose, he adds.

An aspiring pop star, David left India for Beverly Hills in Los Angeles, to record a solo album in Hebrew. He began to get deeper into Judaism, and while he never made it to the pop charts, he found a new calling. One night, he recalls, he had a life-transforming dream about the Lubavitcher Rebbe, enveloped in a bright light. He returned to Israel and enrolled in an Orthodox yeshivah and he joined the ranks of Lubavitch.

Last summer, he returned to Dharamsala as a Chabad emissary to help guide Israeli seekers back to Judaism. “In every religion there’s a spark of truth, and when Jews find it in Buddhism they stop searching,” David tells me. “Judaism can give you all the answers if you give it a chance.”

But Jew turned monk Tenzin Josh believes the answers he’s found in Buddhism have passed the test. “In Judaism, you try to make the best of what God created for you,” he explains, taking a moment away from his study of sacred Tibetan scriptures. “Buddhism encourages you to transcend Creation and become a buddha yourself.”

___________________________________________________________________________________

Ties That Bind

Tibetans hope to learn from the Jewish experience to survive their exile

Tibor Krausz

Jampal Chosang still cherishes the memory. In 1967, he watched enraptured as television screens replayed images of Israeli soldiers driving a numerically superior Egyptian army fleeting back into the Sinai desert during the Six-Day War. A 15-year-old refugee from Chinese-occupied Tibet to Dharamsala's 25,000-strong Tibetan exile community in the Indian Himalayas, he drew immense inspiration from the heroism of a small faraway nation that had returned to its homeland after a long exile and now defended it in forged unity against powerful enemies.

The fascination of Jampal Chosang, today a development officer at the Tibetan Government in Exile in Dharamsala, has grown into a philosophy of self-preservation among Tibetan refugees, who have been uprooted since China’s invasion of Tibet in 1949. It's known as the "Jewish Example": the Jews’ millennia-long striving for a return to Jerusalem has become for Tibetan exiles a ready model for their own longed-for homecoming to Lhasa, Tibet’s capital.

"The Jews," Jampal Chosang tells me in his simple office, framed against the pictures of Mahatma Gandhi and the Dalai Lama, "are the best teachers of survival in exile."

And if the Jews survived the Diaspora through communal solidarity, religious loyalty, and education, the Tibetans have been good students. The 250,000 refugees from the land of snowcapped mountain peaks form close-knit communities in their 50-some settlements scattered around India and Nepal. Galvanized by their spiritual-political leader, the XIV Dalai Lama, they remain steadfast in their Mahayana (“Great Wheel”) Buddhism. And they make Tibetan education freely available to the young: Often, pregnant women from Tibet, where traditions are banned by the Chinese, drag themselves through the Himalayas to give birth in Nepal or Dharamsala, returning home reassured their newborn will grow up imbibing their ancient heritage.

But more than just inspiration in Jewish history, Tibetans also find vital know-how in the greatest modern Jewish experiment — Israel. Since the early 1990s, the Tibetan Central Administration, the nerve center of exile communities, has been sending its cadre to Israel to learn management and leadership skills in month-long programs at the Histadrut Labor Federation, research institutes, and universities. In 1998, in the joint Tibetan-Israeli “Arava Project,” 15 young Tibetan farmers from agricultural settlements arrived in Israel to work for a year on kibbutzim and to master new irrigation, fertilization and crop-growing techniques.

The “Arava Project” has since matured into a permanent program, with 38 Tibetans learning agriculture this year in Israel. Most come from the impoverished, sparsely populated North Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh, a rustic swathe of rugged highlands bordering Bhutan, China and Nepal. The 5,000 Tibetan farmers there eke out a meager existence, clawing the mostly frozen, stone-hard earth to grow maize and measly vegetables.

The hope is that the trainees return home from their stints in Israel armed with the skills to turn their inhospitable landscape into blooming patches of crops. “The kibbutzim made the desert bloom,” explains Ngodup Dorjee, head of planning and development at the exiled government’s Home Department, who was a managerial trainee in Israel in 1994, and now oversees the “Arava Project.” “We’re very enthusiastic to learn from them.”

* * *

“The Yad Vashem Holocaust Museum reminded me of the pictures of Chinese occupation in Tibet,” says Tsering Choezom, a pony-tailed, 16-year-old girl with large chestnut eyes from Ladakh in northern India, now studying in the Tibetan Children’s Village outside Dharamsala. She was one of 12 Tibetan Grade 10 students spending three months last summer at Yemin Orde Youth Village, a modern Orthodox educational complex on Mount Carmel, near Haifa.

The Tibetan students stayed with religious families for Shabbat in Jerusalem’s Old City, had mud baths at the Dead Sea, and prayed at the Western Wall.

“When I prayed there at the wall,” wrote 18-year-old Dawa Dorjee from Mussoorie in North India, in the students’ yearbook after their visit, “I felt I was in front of the Potala Palace” — Tibetans’ revered awe-inspiring monument in Lhasa.

The visitors organized Tibet awareness activities, held discussions with Jewish students, and performed a traditional group dance for Shimon Peres. The Tibetan Department of Education has already selected a new batch of students to visit Israel next summer.

“For our students, who haven’t been outside India before, exposure to Jewish culture is an experience of a lifetime,” says Tsering Phuntsok, a high school principal who escorted the students to Israel and greets me with “Shalom!” “They are very proud to be a bridge between Tibetans and Israelis.”

Many Israelis, too, are busy building bridges. The Israeli Friends of the Tibetan People (IFTIP) have built a whole landscape of them. They initiated the “Arava” agricultural training program and continue to supervise it in Israel. They have sent an Israeli physician to cure the sick in Dharamsala’s Tibetan hospital; a psychologist to develop a study program for children with special needs; and a dentist to provide free dental care.

IFTIP has also built a museum in Dharamsala. Completed in 1998, the Tibet Museum, a compact two-story building on the premises of the Dalai Lama’s landmark Namgyal Monastery, documents the atrocities of the Chinese occupation in photographic and audio-visual exhibits in Hindi, Tibetan and English.

During his visit to Yad Vashem in 1994, the Dalai Lama voiced his desire for a similar museum on Tibet’s tragedy and so IFTIP set to work. Working hand-in-hand with the Tibetans, Israeli museum curators, architects, and volunteers raised funds, designed a building, conceptualized exhibits, initiated an archive, and helped lay the bricks.

“We have a moral obligation, as Jews and Israelis, to assist other nations in need,” says Mikey Ginguld, IFTIP’s Dharamsala-based project coordinator who oversaw work on the museum. “So many of our own people were abandoned in their greatest hour of need (the Holocaust). We can’t let that happen to others.”

In 1988, Ginguld, now 37 and an expert in international development, backpacked it to Tibet, where he witnessed the Chinese violent repression of the Tibetan uprising that March. Deported from Lhasa for pro-democracy activities, he traveled to Dharamsala to brief the Dalai Lama about his experiences. A year later, he set up IFTIP, a volunteer organization that now boasts 300 members and hundreds of supporters across Israel.

In November 1999, IFTIP brought the Dalai Lama to the Jewish State for a four-day visit. “We wanted to inculcate our war-torn region with his aura of peace,” says Yaki Platt, a software engineer and IFTIP’s communications director. The Dalai met Knesset Speaker Avraham Burg and Education Minister Yossi Sarid, despite outraged protests from China’s government.

And outside the glare of publicity, he bonded with Israelis. After a public speech on non-violence in Tel Aviv, Platt recalls, the lama was moved to find a note on his limousine’s windshield and scribbled on it the Hindi “Shalom”: Namaste. Another time, he exchanged his rosary for the tag of a policeman guarding his hotel room.

IFTIP has also started sponsoring 50 poor students in North India and helped enroll two Tibetans for medical studies at Ben-Gurion University. In the works is an agricultural study farm in South India to train farmers in Israeli methods.

* * *

Tibetans’ fascination for Jews reaches back to the early years of their exile. Among the first Western books to be translated into Tibetan (the language of a people isolated for centuries from the outside world) were the Bible and a short history of Israel. When the Dalai Lama started touring the world to solicit international help for Tibet in the early 1970s, he found his first supporters among American Jewish leaders. In 1990, he invited eight of them to his seat in Dharamsala to learn the “Jewish secret” in surviving exile.

Prof. Nathan Katz, chair of Religious Studies at Florida International University, who was a member of the Jewish delegation, recalls: “We told him, ‘Yours is a monastery-centered religion. Unless you take it to the homes, as we took Judaism home from the synagogue, your traditions won’t survive.’”

As the vast majority of Tibetans still live in Tibet, cultural survival may be conditional on another factor: a free Tibet. China, which annexed the country in 1959, suppresses ancient traditions and continues to rule Tibet with an iron fist. It has outlawed Buddhism, destroyed 6,000 monasteries, and “reeducates” imprisoned monks in the enlightened ways of Maoism with whips and electric batons. It controls population growth by forced abortions and sterilization, and has turned the 6 million Tibetans into a minority in Tibet by the transfer of 7.5 million Han Chinese. To date, an estimated 1.2 million Tibetans have died of execution, torture and starvation.

In a break with the Dalai Lama’s Nobel Peace Prize-winning non-violent struggle for autonomy, many Tibetans, far from turning the other cheek, are beginning to see their only hope in armed resistance. Lobsang Galak, a 30-year-old planning officer in Dharamsala, wants to speak to me, gesticulating passionately: “Non-violence is great for international PR, but we need to drag the Chinese to the negotiating table by the nape of their neck.”

He’s for all-out guerilla warfare — Palmach-style. He envisions a Tibetan Liberation Army, modeled on the Zionist paramilitary that had a lion’s share of turning British-mandated Palestine into Israel. A recent graduate of Brandeis University in the U.S., he often sounds more like a Jewish than a Tibetan nationalist. He discusses aliyah, quotes Theodore Herzl, and loves Leon Uris’s modern classic “Exodus.”

“When I read about all the sacrifices the Jews made to regain their land, I ask myself, ‘Are we Tibetans doing enough?’”

Tibetans rose up repeatedly against Chinese rule in 1959 and 1988, unsuccessfully. As China considers the Tibetan Plateau a strategic buffer zone against India, with 200,000 troops and a third of its nuclear arsenal stationed in Tibet, Lobsang Galak’s visions of armed Tibetan liberation will probably remain a pipe dream.

But then, in their restless wait for a cheerful exodus home, Tibetans can always turn to Jewish history for consolation. Says Jampal Chosang: “People tend to lose their hope of ever returning to Lhasa, but we tell them, ‘Look at the Jews. It took them 2,000 years to return home but eventually they did. We will also.”

___________________________________________________________________________________

Shalom Haverim

Tibor Krausz

In 1993, Lobsang Rabsel fled Tibet. Traveling in a group of 20, he set out on foot from Lhasa through the treacherous, snow-bound Himalayas to his destination in Dharamsala. During the grueling, month-long journey, he had only Tibetan tsampa (roasted barley flour) and spring water for nourishment, and had to carry friends who had lost their feet to frostbite.

His reason for escape? To help preserve his people’s culture in exile.

Now in “Little Lhasa,” as the exiles call Dharamsala, he’s doing the same for another people. Every Friday morning, the short, thin man who manages Khana Nirvana Café on Dalai Lama Temple Rd. in Mcleod Ganj, a vibrant Tibetan village 30 minutes uphill from Dharamsala, trots up the dirt road to the town’s center, past ramshackle souvenir stalls and leprous Indian beggars with fingerless hands. There, he starts scouting for Israelis. He hands them flyers, inviting: “Please come to Kabbalat Shabbat!”

At sunset, back in the small, wood-paneled vegetarian restaurant, he greets Jewish arrivals with a happy “Shabbat Shalom!” He lights candles, and asks an Israeli wearing a kippah to say Kiddush for the 20 other Jews gathered there, as portly Tibetan grandmas are baking challah bread in the open kitchen. The cheerful gathering then sings “Y’ase Shalom” . . . and discusses Buddhism.

Another Shabbat in the Himalayas.

And another success for Azriel Cohen, a world away in Jerusalem. Cohen, 35, a Toronto-born painter-photographer and an Orthodox Jew from a family of rabbis who lives in Jerusalem, had a lofty idea when he first visited Dharamsala in 1996. Troubled by Jews’ extensive forays into Buddhism, he sought to create a haven of Judaism in the home of lamas. He set up Ohr Olam (“A light onto the world,” Isaiah 60:19) in April 1997, from donations he’d raised in a dozen Orthodox synagogues in Canada and the U.S.

The former yeshivah student then approached Khana Nirvana’s American Jewish owner for space to his new outreach programs. Now, the café offers a 250-book Jewish library in Hebrew and English as well as a large collection of taped Jewish lectures and songs. Its kindly Tibetan staff carries on Cohen’s mission in his absence.

* * *

In recent years, Dharamsala has become a hotspot for Jewish spiritual seekers, thanks to the Dalai Lama’s fame and the mystique of esoteric Tibetan Buddhism, which features maroon-robed monks, a state oracle, ancient pearls of wisdom, prayer wheels, and mantra flags inscribed with an exotic script.

“Little Lhasa” seems like “Little Israel” at times, with Hebrew more prominent than Hindi. Vendors and waiters offer services in the vernacular and most street signs sport Hebrew letters. Locals often greet Israelis with “Shalom,” and the Jews return the favor with “Tashi Delek,” the Tibetan hello.

Cohen, who has since 1996 returned to Dharamsala four times for a total of one year, estimates that three in four Western visitors are Jewish. Many come just to tick off the town on their Indian “must-go” list, but quite a few come in search of the dharma, Buddha’s teachings.

For High Holidays, Cohen, a lanky energetic man with bushy hair, arrives back in town, armed with matzo, kosher wine and Jewish paraphernalia. He visits monasteries, meditation retreats, lecture halls and popular local hangouts to invite Israelis for religious services. At Rosh Hashanah, the boom of his shofar echoes through the beautiful, pine-clad Kangra Valley. Following each boom is the murmur of kavanot (Jewish “mantras”) as Cohen leads dozens of Jews in meditating on the divine purpose of prayer, based on Jewish mystical traditions.

His Yom Kippur in Mcleod Ganj finds many Jews fasting resolutely amid the delicious oriental staples of Khana Nirvana, which always remains closed on Saturday. Last Passover, Cohen drew a crowd of 350 Israelis for the Seder in the hall of a nearby Tibetan school, and organized interfaith dialogues between Buddhists and Jews, where an Israeli-turned-monk shared the podium with the local Chabad emissary.

“I’m not into a messianic vision of bringing all Jews back,” Cohen tells The Report. “All I want is create an environment that’s as welcoming to a Haredi Jew as to a Jewish-born monk.”

His drive for Kiddush Hashem (sanctification of God’s name) in Dharamsala has received widespread support from the local Tibetan Buddhist community. In his private meeting with the Dalai Lama in 1997, when Cohen asked the celebrated monk’s permission for his local Jewish activities, the dalai gave his blessing: “My pleasure! You are the chosen people. Not true?”

Ram Swaroop, a prominent local Indian businessman who has watched Ohr Olam’s development, has now offered space on his property for Cohen to construct a permanent center and extend his interfaith activities in order “to provide an example of how different religions can express themselves fully side by side.”

Just what Cohen has in mind. “We each hold a small piece of the cosmic puzzle,” he explains. “Whether Buddhist or Jew, we each have what to teach others. By God’s will, we’re each unique for a reason. Let’s see what happens if we try to embrace that idea.”

Count Lobsang Rabsel in for it.