Zion on the Myanmar Border

On a rare visit to the B’nei Menashe of northeast India, Tibor Krausz meets members of the ‘Lost Tribe’ of Mizos and Kukis, erstwhile headhunters who are pursing Judaism with a rapidly deepening fervor as they wait to make aliyah

Tibor Krausz

The Jerusalem Report, November 17, 2003

The hand-painted letters on the shutters of the “public phone service” announce “Sabbath close.” On any other day locals can call long-distance for 42 rupees (around $1) a minute from the worn touchtone phone at this little convenience kiosk. But today is Shabbat and the booth’s owner is at home in a sparse cinderblock cubicle at the back, which serves both as a tin-pot kitchen and a single-cot bedroom, and is dissected diagonally by the underside of stairs belonging to the residence above. She’s a petite woman in a knitted white cloche, and is just saying kiddush over Styrofoam cups of grape juice and chocolate-cream biscuits, beneath a Xeroxed pin-up of the Ten Commandments rendered into the Mizo tongue.

She then recites the Shabbat blessing over her two young sons in phonetically memorized Hebrew: “May God make you like Ephraim and Manasseh.” She utters it matter-of-factly; the very words, however, are being plenty poignant: 35-year-old Esther Thangluah believes herself to be a far-flung descendant of the biblical Manasseh, father to one of the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel. She’s now reclaiming that ancient heritage as a member of the 5,000-strong B’nei Menashe (Children of Menashe) community living in the adjoining states of Mizoram and Manipur in northeast India.

Pearly teardrops escape from her eyes. “I always cry in longing to return to Zion,” she apologizes through her interpreter, Elisheva Zodingliani, 45, a fellow B’nei Menashe. “But I’m crying tears of joy.”

Zodingliani, too, begins to weep. “With all our hearts, souls and minds” she says, “we’re children of a Lost Tribe.” Bespectacled and prissy, she resembles a stereotypical schoolmarm; indeed she homeschools some 30 fellow Mizos in basic Hebrew and publishes Israel Tlangau (Israel Herald), a thick newsletter carrying primers about Jewish customs, news from Israel, and B’nei Menashe community updates. “Please let us go to Israel,” she pleads. “We’re strangers here, feeling in exile in our own homeland.”

Thangluah, a onetime Seventh-day Adventist, found Judaism in 1992, after, she says, receiving a recurrent vision in which she saw the Mount of God sheltering the Chosen of Israel in an apocalyptic thunderstorm. She was living in Ratu, her native village in northern Mizoram, where four decades earlier a Pentecostal Christian called Chala “the Mizo Prophet” had received his own vision about an angel who revealed the Mizos to be a Lost Tribe, thereby inspiring a spiritual movement that has since transformed the life of a once isolated, inward-looking people. Convinced she was spiritually a Jew, Thangluah began searching for an observant B’nei Menashe community and in Aizawl, the capital of Mizoram, she’s found one.

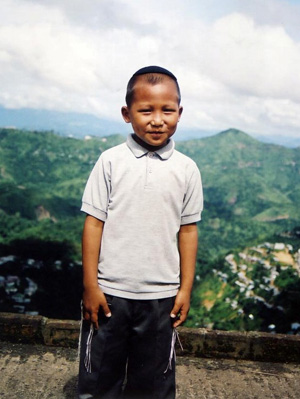

“We pray to Hashem every day to help us return to Israel,” she repeats. “We” means herself and her sons, Dael, 11, and Samson, 7. The boys, who’re wearing crocheted yarmulkes and tzitzit, speak with a gravity far beyond their age. Earlier this year they had their circumcision, they say. “My mommy told us we had to obey Pathian,” explains Dael, using the Mizos’ traditional name for God. “I want to follow His laws and teach others to do that, too. I want to be a rabbi.”

Dael and Samson study fulltime in the nearby Amishav Hebrew Center, a four-story yeshiva run by the eponymous Jerusalem-based outreach organization, which for B’nei Menashe students serves as a latter-day incarnation of the traditional zawlbuk (bachelors’ dormitory), where Mizo youth once learned their lessons for their tribal rites of passage. But these boys now receive their formative ideas from Orthodox Judaism — only doodles of Batman crayoned on the pockmarked wall above their shared bed betray alternative childhood dreams. “I teach my sons they’ll have to become soldiers and defend Israel,” says Thangluah in between singing Hebrew songs and tending to her meager crop of edible hibiscus, bitter cucumber and balsam-apple sprouting from tin oilcans in her asphalted roof terrace “garden.”

* * *

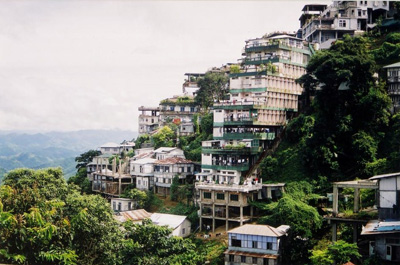

Around the Indian state of Mizoram, a mountainous strip of land wedged between Myanmar and Bangladesh astride the Tropic of Cancer, lush primeval forests lurk in ambush at the edges of human habitation to reclaim soil lost to rice paddies and hanky-size patches of squash, sugarcane and mustard that surround hamlets on stilts.

Aizawl, whose inhabitants are predominantly pious Christians, takes on the trappings of a surreal Zionist shtetl. The city has localities called Canaan and Beth El, and its main thoroughfare is Zion Street. It’s a busy, zigzagging, up-and-down road where abrupt ankle-twisting flights of stairs yawn suddenly in narrow sidewalks threatening to suck in unwary pedestrians; on it, so many Israel Shops and Stores ply their trade, peddling everything from footwear to haberdashery.

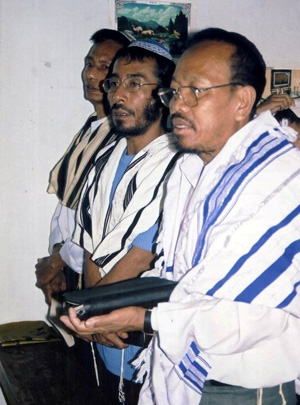

And there’s the Shalom Zion Synagogue. It’s the center of the small community that has taken its fascination with the Torah and modern-day Israel to the next level by declaring itself Jewish. Overlooking a valley covered in huts nestled among giant ferns, the large wood-framed affair with its corrugated iron roof stands on stilts atop the naked concrete skeleton of a far larger synagogue in the making. It’s Friday evening, but today is no ordinary Shabbat. “Mizoram Welcomes Rav Eliyahu Avichail, the Father of B’nei Menashe” proclaims a sign outside; a solemnly festive atmosphere reigns inside. Wearing knitted yarmulkes, dripping with tzitzit, and wrapped in prayer shawls.

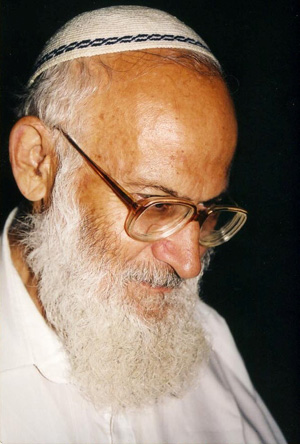

In town for the ninth time since his first visit in 1992, Rabbi Avichail, a 72-year-old Bible teacher turned Lost Tribe hunter from Jerusalem, is regaling them with stories from his worldwide travels in search of lost Jews over the past 20 years. Gesticulating spiritedly with his slender manicured fingers, he tells them how he was taken for a spy in Kashmir, where he was seeking a Lost Tribe. How he broadcast a message on the Voice of America to the Pashtuns of Afghanistan to inform them they were descendants of Jews.

But most already know this latter tale well; after all, an originator of that letter is sitting right here among them. A neatly groomed senior accountant, Yehoshua Ngaihte, 61, founded the Israel Family Association in 1972, proclaimed its members B’nei Menashe, and appealed unsuccessfully for help to Bene Israel communities in Bombay, to the Jewish Agency, and finally to David Ben-Gurion. “Hashem first revealed to me we were Children of Menashe as I was lying in bed with malarial fever,” Ngaihte remembers. (Shamanist-animists turned Christians from Presbyterians to Jehovah’s Witnesses, locals attach great importance to their dreams, interpreting them as visions and revelations.) He received his vision in rural Manipur independently, he insists, from Chala’s own vision two decades earlier in Mizoram.

More certainly Rabbi Avichail has. Spearheading the Jerusalem-based Amishav (My People Returns) — which he founded in 1975 on the request of his mentor, Rabbi Tzvi Yehuda Kook, with a view to bringing “lost” Jews to the Promised Land — he has single-handedly internationalized the Lost Tribehood aspirations of an obscure faraway people, while also entrenching locals in their beliefs.

Before he came along, the folk tradition of Mizos (a melange of a dozen interrelated tribes whose collective name means “highlanders”) had maintained their ancestors emerged from under a rock, the chhinlung, corking up the portal to the underworld in southwestern Rabbi Avichail thought otherwise. Marrying his Lost Tribe theories to Mizo folktales, he mapped out the tribe’s putative route from Israel: after wandering through Afghanistan, the Himalayas, MongoliaInvigorated by this rabbinic seal of approval, from the mid-1980s the tiny original B’nei Menashe communities in Mizoram and Manipur started swelling up with increasing numbers of Mizos and Kukis (living respectively in Mizoram and Manipur who, along with the Chins of Myanmar, have been collectively called the Shinlung by outsiders).

The newcomers announced themselves B’nei Menashe, underwent circumcision, and began observing Shabbat in makeshift synagogues; much of the larger Christian community also came around to endorsing newfound Israelite descent. “All Mizos love Israel,” asserts Henry Lalbuanga, 34, a shaven-pated burly construction engineer.

Others have launched into collecting old folktales and traditions to comb them retroactively for any similarity to Israelite customs in the Bible. They “discovered” their ancestors had been proto-monotheists even before converting to Christianity, offered animal sacrifice to a supreme god called Ya, and invoked the name of a mysterious ancestor called Manmase or Manasia at every ceremonial opportunity.

Not even such blatantly non-biblical tribal customs as headhunting (still practiced in the early 20th century) stood in the way of proof. “Didn’t David also cut off the head of Goliath to prove he’s slain him?” asserts Zaithanchhungi, 60, an amateur historian and the Mizos’ leading homegrown authority on their putative Israelite descent.

Yet for all that, many Mizos, while embracing their self-proclaimed biblical heritage, clearly feel the need to fortify their beliefs with confirmation by disinterested outsiders. “Do you think we’re a Lost Tribe?” is a staple query to Jewish foreigners.

Rabbi Avichail harbors no doubts, and under his tutelage untold numbers of them have been fortified in their mounting belief. In 1989, with Mizoram still off-limits to outsiders because of a simmering anti-Indian insurgency, Avichail dispatched a rabbi to Bombay to convert 24 Mizo men and women to Judaism, who were allowed to make aliyah the same year. “The Mizos aren’t Jewish,” Avichail allows. “Yet they’re descendants of Jews, so after undergoing conversion they must be permitted to return to Israel.”

* * *

In the Amishav Hebrew Center, uphill from Zion Street, the poster of a conceptualized Third Temple hangs over a miniature replica of a traditional Mizo bamboo hut; the placing is coincidental, but not so their implied kinship. Avichail sees the B’nei Menashe’s heady emergence as proof for the end-of-days ingathering of the exiles to Israel, which heralds the coming of the Messiah and the construction of the Temple.

The B’nei Menashe in turn revere their mentor and “discoverer” as a latter-day Moses who will lead his long-mislaid flock back to the Promised Land — planeload by new planeload. (A new batch of 71 Mizos arrived in Israel last June.) “Rabbi Avichail is our beram vengtu [shepherd],” volunteers Eliezer Sela, the community’s 60-year-old cantor who renamed most of his nine children (now between the ages of 20 and 36 and all of whom have made aliyah) after “heroes of Israel,” calling them Allenby Sela, Gurion Sela.

Former semi-nomads who continue to practice slash-and-burn jhum cultivation, locals have never made a secret of not feeling at home in India, where ethnographers say they arrived from China via Burma only around four centuries ago. Soon after a plaque of rats — their ranks swelled by a rare flowering of bamboos.

Every time he lands at Lengpui Airport, an airfield 42 km downhill from Aizawl, hundreds of cheery locals await him, waving Israeli flags, chorusing “Shalom Aleichem,” and rejoicing at the mere sight of him. When on a previous visit he came down with severe food poisoning, teary-eyed dozens kept vigil around his sickbed. They address him deferentially as ha-Rav, and once named a synagogue after him.

Avichail, an alternately a peppery man (who with his potbelly, snow-white beard, and twinkling blue eyes could moonlight as a shopping-mall Santa), mingles among his prot‚g‚s with the bearing of a biblical patriarch. He arbitrates and adjudicates, counsels and educates.

Right now, his left arm grabbing a Mizo boy, his right arm supporting a man his age, the old rabbi gambols gaily about, kicking up his heels and belting out — in a hundred-mouth chorus of merrymakers — “Shabbat Shalom! Shabbat Shalom!” at a decibel enough to rupture your eardrums.

“I’m 72, and who knows how long I may continue to guide them,” he says, panting. “But with or without me, they’ll have to carry on until they’ve all made aliyah.” Amishav has enrolled five Mizos in Jerusalem yeshivas, soon to return home as rabbis to help bring all of Mizoram’s and Manipur’s B’nei Menashe to Israel by 2010.

“The B’nei Menashe are knocking at our national door, asking to be allowed in,” avers Amishav Director Michael Freund, once a deputy communications director for former prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu. “It’s time we let them in; Lost Tribes like them may well provide us with the answer to preserving a Jewish majority in Israel.”

Yet Israeli immigration officials remain skeptical of the Mizos’ claims. Even after they’re converted by Israel’s Chief Rabbinate, only willy-nilly does the government recognize their right to the country’s Law of Return. But Rabbi Avichail is as undaunted as ever. “Let the government try to stop me,” he declares. “It’ll crumble before the strength of my beliefs!”

* * *

A year ago Peter Zokhuma quit his job as an electrician for a local World Bank project, and by now he’s used up almost all his savings. But in the process, he says, he’s made a priceless investment: as one of Amishav House’s 200-plus fulltime students since the building opened its doors last November, Zokhuma, 47, has learned basic Hebrew and schooled himself in Torah studies by help of the dozen (and counting) religious textbooks translated by Amishav into Mizo.

When one evening during classes a power outage kills lights in the building, he hurries out of his classroom. But it’s not to fix a blown fuse; momentarily, he returns with candles. By their dim flicker he continues to pore over his Hebrew primer, alongside his three sons, the youngest of whom, Mordechai, is only four. “I trust Hashem to help my family,” explains Zokhuma, a dark-skinned clerkish man.

So would thousands of others. “A wizened old man who was near-blind from cataract and leaning heavily on a bamboo stick shuffled up to me and grabbed me by the arm,” recounts Hanoch Avizedek, a 40-year-old organic olive farmer from the Jewish settlement of Ateret, near Ramallah, who’s on a six-week stint in Aizawl as a Hebrew and Torah teacher for Amishav. “The old man said, ‘I’ve walked a great distance just to see a Jewish face perhaps for the last time. Tell me, when can I go to Israel? I’ve been waiting 40 years.’ He cried and I cried, too.”

The encounter happened during a tour of the neighboring state of Manipur that Avichail and his entourage had undertaken a few days earlier. Rural Manipur is a patchy network of hamlets fashioned from thatch, bamboo, and wattle, many of which seem poised to melt back into mud and mulch — and it’s a prohibitively dangerous land. Some two dozen rebel band prowl the jungles, engaging in banditry, running drugs, and staging ambushes on Indian patrols and rival paramilitaries. Into this Wild East rolled a caravan of jam-packed buses bedecked in Israeli banners, flanked by armored military jeeps, and announced miles ahead by blaring Hebrew songs.

Heading up a 200-strong delegation of Manipuri notables and B’nei Menashe groups from Imphal, the state capital, Avichail was calling on his flock in villages with names like Phailen, Muolkoi, Vengnom — and Hebrew ones like Moshav Hamore and Zohar.

Rattling along rutted dirt-tracks, he whizzed in and out of hamlets built around thatched mud-walled synagogues often housing little more than wooden menorahs garlanded with dry leaves. Under hand-painted signs “May Our Dear Rev Live Long!” he lectured to barefooted subsistence farmers and officiated at services using the locals’ Torah scroll photocopies.

And he inspected the memorials erected around Manipur in his honor, from improvised steles to extravagant obelisks commemorating “the 25th Anniversary Foundation of Judaism in Northeast India”Before I accepted Rabbi Avichail’s invitation to come here, I thought of him as some eccentric Dr. Doolittle,” comments Avizedek, a bearish, bushy-bearded man who refers to Mizos and Kukis as “my brothers and sisters.” “But the rabbi has worked magic here. I’m a simple farmer, but people come and touch me as if I was a great holy rebbe just because I’m an Israeli.”

Visible through an open door of Amishav House back in Aizawl, Mizo men are participating in the evening prayer, acting with the confidence of autodidact liturgists blessed with the talents of mimics. “I lectured them on some esoteric points of Kabbalah (at classes in the Hebrew Center),” Besancon continues. He’s a large Kabbalist with disheveled gray hair crowned by a pointy pompomed skullcap.

In contrast to Poland, though, stalwart Christians too profess to love everything Israeli. Veronica Zatluangi, a retired Roman Catholic civil servant, runs an orphanage and lives in a small gingerbread-style chalet erected on the flat concrete roof of Amishav House, which she owns. “The Indian government wanted to rent my building for 45,000 rupees ($1,000) a month, then [Amishav Director] Michael Freund came last year, offered me 25,000 rupees, and I happily gave it to him,” she enthuses, flashing a betel-reddened smile. “When I built the house, an old wise neighbor told me, ‘One day the Children of God will live in it.’ And see, here they are!”

After a 10-day stay, Rabbi Avichail leaves Aizawl. Yet his charges in Amishav House appear none the worse for his absence: they continue to study and pray as studiously, sing and dance as merrily, as before. And why not? The rabbi has left behind for them a great gift — the promise that one day they too can join their brethren in Israel.

___________________________________________________________________________________

Zionism Revisited

Tibor Krausz

The headquarters of the Israel Democratic Party in downtown Aizawl is a wood shack atop a stationary kiosk. But the humble offices of Mizoram’s homegrown Zionist party (where the only decoration is a wall-mounted group photo of Mizo Israelis in IDF uniform) belie its grand aspirations.

“We intend to declare Mizoram the Second State of Israel,” pledges Party President Zailiana, a one-armed evangelist pastor with a traditional single name whose face and chest still bear the deep scars of a recent motorcycle accident.

“We’ll be campaigning to officially rename Mizoram Lushai Hills Israel.” (Lushai Hills was the name missionaries gave to Mizoram and Manipur when in the late 19th century they began converting the local slave-owning headhunters to Christianity; intriguingly, “Lushai” means “ten tribes” in Burmese.)

If, that is, his party wins his hoped-for five seats in the 40-member General Assembly at state elections slated for early next year. President Zailiana claims that the IDP, which he founded in 1998, already has 40,000 (Christian) supporters in 40 constituencies. Home Minister Tawnluia, from the ruling Mizo National Front, he adds, has already said yes to a name-change for Mizoram — although a qualified yes, predicated on election results and political viability.

“Whether Christian or Jew, we’re Children of Menashe, and our life and blood belong to Israel,” he proclaims, adding: “But not all of us want to go and live there; instead, our party wants to bring Israel to Mizoram.” He’s running for office on a platform of increased cultural and trade relations with the Jewish State. As a highlight of this campaign, the IDP has just staged a public tribute rally at Aizawl’s 3,000-seat Vanapa Hall in memory of astronaut Ilan Ramon.

You may be forgiven for regarding the Israel Democratic Party as the brainchild of misguided enthusiasts, or political crackpots. Until you meet Mizoram’s head of state. Chief Minister Zoramthanga, a small dapper man, receives me in his baronial hacienda atop Aizawl’s highest peak. “We derive our inspiration from the faith of Abraham and the political experience of Israel,” he declares. “In our struggle for independence, we took leaves out of Israel’s book.”

He means this literally. While second-in-command of the Mizo National Front (then a separatist liberation movement) in the 1966 rebellion against Indian rule and in the ensuing two decades of guerilla warfare, he carried a dog-eared copy of “Exodus” by Leon Uris. Holed up in jungle hideouts, he would read passages out loud to his fighters to restore their sagging morale during seemingly fruitless, interminable fighting. “We learned leadership skills from David Ben-Gurion and Golda Meir,” he says. “And we tried to emulate the bravery and ardor of Israeli soldiers.”

On the run in the 1970s from India’s secret service, Zoramthanga even considered seeking political asylum in Israel. He and his fighters laid down their arms in 1986 after India agreed to grant autonomy to Mizoram — but the Chief Minister is learning still. “Just like Israel, we’re past fighting for independence and into nation-building. Now we have to learn how to turn our state into a land of milk and honey.”

___________________________________________________________________________________

Are They or Aren’t They?

Tibor Krausz

They believed in a single all-powerful deity whose name was taboo. They circumcised their newborn on the eighth postnatal day. They had priests who practiced levirate marriage and offered animal sacrifices to God. Are we taking about biblical Israelites?

Yes and no. No, because these singular attributes of pre-rabbinic Judaism were once allegedly practiced by interrelated tribes in the Indian states of Manipur and Mizoram and Burma’s Chin State. Yes, because numerous tribespeople now profess to be scions of the Tribe of Menashe, one of the Ten Tribes of Israel sent in 722 BCE by the Assyrians into permanent exile, where they were lost to history. Until recently, perhaps.

Inspired by some of their leaders’ “revelations” beginning in the 1950s that the Mizos, Kukis, and Chins were Children of Menashe, increasing numbers of locals began endorsing their newfound Israelite identity; and a quarter century ago a handful decided to seek confirmation from true-blue Jews. Confirm their beliefs Rabbi Eliyahu Avichail did. Using Biblical and Talmudic sources and acting on his modus operandi that “We have to locate people who show Jewish sings and convert them to Judaism,” he pronounced them a Lost Tribe Found and adopted as his own their cause to return to Israel.

Then again, make both that yes and no above two very speculative maybes. All the evidence is at best circumstantial. Though, for one, Zaithanchhungi, 60, a headmistress turned historian (and practicing Presbyterian) in Aizawl who like numerous Mizos has a single name, has collected a book’s worth of it in her “Israel-Mizo Identity,” a bestseller in Mizoram. “From birth to burial, we had numerous customs matching those of Israelites in the Bible,” is the conclusion she drew after interviewing village elders across Mizoram (on Avichail’s request) to learn about pre-Christian tribal customs.

For example, she says, on the eighth day after a newborn’s birth a priest would pass him through a loop of vine and offer him to Pathian, the Mizos’ almighty yet elusive Great Spirit, whose secret name was Ya.

Some elders also recalled witnessing in their youth “proper circumcision,” during which a village priest pierced a newborn’s foreskin with a porcupine quill. Or take animal sacrifice: In time of disease, hereditary priests who belonged to a single clan (like Aaronite priests) would depart to a bamboo altar outside the village “where pigs wouldn’t roam,” slaughter a sacrificial chicken and call out: “Pathian on high the Children of Manasia” — or sometimes Manmase — “offer you the blood of this animal.” “‘Who’s this Manasia?’ They replied: ‘We don’t know. Perhaps our ancestor,’” she says. Equate Manasia with Menashe (as Rabbi Avichail did) and you’ve found a Lo

“It’s all just a spiritually misguided attempt to give ourselves an identity we don’t have,” counters Boichhingpuii, the director of Aizawl’s Tribal Research Institute. “How come we had a so-called Red Sea song [which mentions tribes crossing a wide sea], but never heard of the Ten Commandments? That we supposedly remembered Menashe, but forgot about Abraham, Moses and David?”

Hillel Halkin had been a skeptic, too. Until his research convinced him otherwise with a “107 percent” certainty. In his recent book “Across the Shabbat River” (Houghton Mifflin, 2002), the American-born Israeli journalist, who set out to prove or disprove the B’nei Menashe’s claims, argues the local tribes are indeed related somehow to biblical Israelites.

He does so on the basis of a Manipuri amateur ethnographer’s anthology of old word-of-mouth folktales, which contain garbled stories of a red-earth man, a prehistoric garden, a flood, and the exile of tribes from the “land of oil and rich soil.”

Recently, writing side-by-side in the Biblical Archeological Review, Rivka Gonen, an Israeli ethnographer, and Ronald Hendel, an American philologist, panned Halkin’s findings. And even Halkin suggests there’s no way of proving his case short of genetic testing. A “Jewish” marker Y chromosome has been shown to have lived on in Jews throughout the Diaspora; Halkin is planning to take Israeli and American geneticists to Mizoram and Manipur to test the locals for it.