Paradise Found

In a lush valley beneath an extinct volcano in northern Iran, groundbreaking British archaeologist David Rohl claims to have found the site described in Genesis as Eden. And while there's no shortage of skeptics, several leading experts are more than intrigued

Tibor Krausz

The Jerusalem Report, February 1, 1999

"The Lord God planted a garden in Eden, in the east, and placed there the man whom He had formed'' "A river issues from Eden to water the garden, and it then divides and becomes four branches. The name of the first is Pishon, which winds through the whole land of Havilah. The gold of that land is good; bdellium is there, and lapis lazuli. The name of the second river is Gihon, which winds through the whole land of Cush. The name of the third river is Tigris, which flows east of Assyria. And the fourth river is the Euphrates."

Genesis 2:8-14

The route: From western Iran, north through the Zagros mountains of Iranian Kurdistan, down Mt. Sahand, and into the fertile Adji Chay valley.

The destination: Eden.

Ten miles from the sprawling Iranian industrial city of Tabriz, to the northwest of Teheran, says British archaeologist David Rohl, he has found the site of the Biblical garden. And while many experts have their doubts, several respected historians and geologists are convinced that Rohl's assertions have real merit.

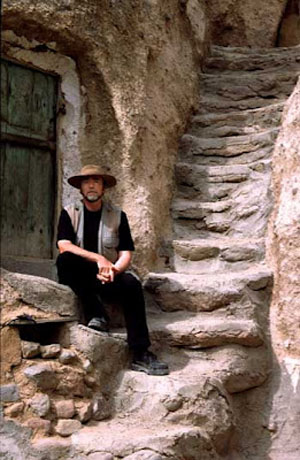

"As you descend a narrow mountain path, you see a beautiful alpine valley, just like the Bible describes it, with terraced orchards on its slopes, crowded with every kind of fruit-laden tree," says Rohl, a scholar of University College, London, who has just returned from his third trip to the area, where mud-brick villages flourish today.

"The Biblical word gan (as in Gan Eden) means 'walled garden,'" Rohl continues, "and the valley is indeed walled in by towering mountains." The highest of these is Mt. Sahand, a snow-capped extinct volcano that Rohl identifies as the Prophet Ezekiel's Mountain of God, where the Lord resided among "red-hot coals" (Ezekiel 28:11-19). Cascading down the once-fiery mountain, precisely echoing Ezekiel, is a small river, the Adji Chay (the name of which also translates in local dialect as "walled garden"). The locals still hold the mountain sacred, Rohl says, and attribute magical powers to the river's water.

The word Eden itself, Rohl believes, likely derives from the Sumerian "Edin" or "fertile plain." Read properly, he asserts, the Bible places the primordial garden on the eastern side of a fertile plain. And, true to form, his valley is just to the east of the 200- mile-long Miyandoab plain, which lies alongside two great salt lakes, Urmia and Van, on the borders of Iran, Iraq and Turkey. "In prehistoric times, the climate there was much warmer and wetter than today," Rohl told The Jerusalem Report. "Dense pine and cedar forests covered the slopes of the valley, which no doubt nurtured an earthly paradise."

Even today the valley is lush; it serves as Tabriz's kitchen garden. But pollution from nearby petrochemical plants, Rohl says, makes it "paradise lost." In a sad sense, that's fitting, because as Rohl reads the story of Eden, it's about the "descent" of humanity, from a pristine existence as hunters and gatherers, into urban living.

* * *

The Garden of Eden is not on most scholars' list of archaeological targets. Conventional scholarly wisdom considers the search for Eden as futile as would be the search for the Hades of Greek mythology. Eden, skeptics say, exists strictly in the realm of faith and myth, and should be left there. "I doubt we'll ever find Eden outside the pages of the Bible," asserts Prof. Victor Hurowitz, a Biblical scholar and Assyriologist at Ben-Gurion University in Beersheba. "Scholars who go looking for it end up imposing the myth on the facts on the ground."

Yet Rohl, an Egyptologist who came to his site partly by following the researches of the late, little-known British scholar Reginald Walker, and partly by retracing a 5,000-year-old route to Eden described in Sumerian cuneiform clay tablets held by the Museum of the Orient in Istanbul, is only one of an increasing number of archaeologists, geologists, historians and others who insist Eden does have a physical dimension. The "Edenists" who include the American archaeologists Prof. Juris Zarins and James Sauer, and the populist British author Andrew Collins don't claim for a moment that man was created there, or that the events in Eden unfolded as the Bible describes them. But they emphatically argue that Genesis, in describing Eden, had a specific place in mind just as Homer was speaking of a real Troy in the Iliad, though the city was regarded as a mythical place until its ruins were discovered. (See box, page 41).

Since the Bible scrupulously documents the specifics of the garden's location and its surroundings, says Rohl, a non-practicing Catholic, why shouldn't we take those descriptions at face value? "I consider the Bible a historical document just like the writings of Herodotus or a text of Rameses II," says Rohl, who has just published his findings in "Legend: The Genesis of Civilisation" (Century) in England. "It's ridiculous to throw it in the dustbin just because it's a religious text. If so strong a tradition evolves out of the past, it is likely to have a genuine geographical setting."

The Biblical description places Eden at the headwaters of four rivers: the Tigris (Hiddekel in Hebrew), the Euphrates (Perat), the Gihon and the Pishon. The Tigris and the Euphrates, which both rise near Lake Van and empty into the Persian Gulf, are no-brainers; the Gihon and the Pishon are anyone's guess. The first-century Jewish historian Josephus Flavius identified them as the Nile and the Ganges; ever since, scholars and clerics have wagered on most major rivers in Western Asia.

Rohl identifies them as the Araxes, which flows from north of Lake Urmia to the Caspian Sea to the east; and the Uizhun, which rises near Mt. Sahand and also disgorges into the Caspian. That puts the headwaters of all four rivers at his Eden. "I'm convinced that the Garden of Eden has finally been discovered," Rohl asserts. "Not only have we identified the four rivers, but the topography fits the description of an Edenic paradise perfectly."

The area, Rohl adds, is also packed with landmarks that retain their Biblical names. North of the Adji Chay river valley rises the Kusheh Dagh the Mountain of Kush. Beyond it lay the Bible's land of Cush, Rohl asserts, rejecting the traditional identification of Cush with Ethiopia. The Araxes, the Bible's Gihon, "winds through" the area, just as the Bible describes. The Uizhun, Rohl's equivalent to the Bible's Pishon, is known locally as the Golden River, and meanders between ancient gold mines and lodes of lapis lazuli. Again, this matches the Bible's account. And "East of Eden," not far from Tabriz, Rohl has found an area called Noqdi, which he believes is the Biblical land of Nod Cain's place of exile after murdering Abel.

Rohl goes even further: A few kilometers south of his putative Nod, at the head of a mountain pass, lies the sleepy town of Helabad, formerly known as Kheruabad "settlement of the Kheru people." That, he says, could be a permutation of the Biblical word keruvim the ferocious winged guardians of Eden's eastern gateway. Genesis is normally read as referring to some type of angel, but Rohl suggests that the keruvim, or Cherubs, were a tribe of fearsome warriors whose token was an eagle or falcon, and who were only turned into otherworldly creatures by later tradition.

Several leading historians in Britain, where Rohl's theory is gaining widespread popular and scholarly attention, find much that is convincing in his arguments. "There's a very good chance that Rohl is right on the topography," says the University of Liverpool's Prof. Kenneth Kitchen, a world-famous historian of the ancient world. "But to guarantee it with absolute certainty, I'll just have to scratch my head until the rest of my hair disappears." David Ellis, director of the Genesis Laboratory in London, a center of research on the origins of civilization, agrees: "Rohl has correctly identified and fitted together several pieces of the jigsaw puzzle. Civilization did originate in this area, and that makes for an intriguing hypothesis."

Leading Israeli archaeologists, meanwhile, are so taken with the claims that they have told The Report of plans for a conference on Eden in Jerusalem this summer, which Rohl says he intends to attend. "Discoveries like this are the biggest draw for archaeology," says organizer David Ilan, an archaeologist at Hebrew Union College.

* * *

David Rohl is not new to Biblical headline making. Three years ago, he stood the accepted chronology of ancient Egypt on its head by claiming that shortening the pharaonic timeline by up to 300 years results in perfect matches between Egyptian history and Biblical narratives, including the life of Joseph, the Exodus and the conquest of the Promised Land by Joshua. He argued his case in a controversial bestseller "A Test of Time" and the subsequent TV series "Pharaohs and Kings," which made him Britain's highest- profile archaeologist and the center of much scholarly feuding.

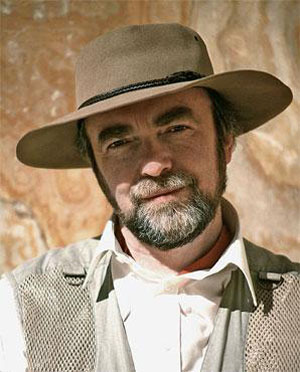

Bearded and over six feet tall, Rohl, 48, caught the ancient history bug as a nine-year-old, when his mother took him on vacation along the River Nile. Nowadays, he scouts around the Middle East in a weather-beaten fedora and says he loves the "adventure of archaeology." But he chafes at the unavoidable comparison with Harrison Ford's celluloid adventurer Indiana Jones: "Jones is a robber. He steals artefacts; he doesn't discover them. Archaeology is a painstaking accumulation of evidence, not a gung-ho fantasy world," he says.

Still, Rohl's Eden quest does rival some of his Hollywood alter ego's exploits. He had been researching the location since the late 1980s through academic documents. But in April 1997, he decided to seek out Eden himself, and set out from the Iranian town of Ahwaz, near the northern tip of the Gulf, with only his jeep driver for company. They traveled north toward Kurdistan through what Rohl calls "lawless" terrain, trusting to luck to avoid the various guerrilla factions active in the region.

Rohl was following a route, documented in the Sumerian cuneiform epic "Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta," supposedly taken 5,000 years earlier by an emissary of the Sumerian priest-king of Uruk. The emissary had been dispatched to Aratta, on the plain of "Edin" known to Sumerians as a land of happiness and plenty to obtain gold and lapis lazuli to decorate a temple that Enmerkar was building in Uruk, a Sumerian city-state on the plains between Kurdistan and the Gulf. The cuneiform epic describes the dutiful emissary's three-month trek on foot via seven passes through the Zagros mountains, to the foothills of Mt. Sahand the southern edge of Rohl's Eden and his successful procurement of the required valuables.

Rohl believes that this account inspired the Seven Gates of Heaven motif in Talmudic tradition thousands of years later. "The ancient Sumerians, Babylonians and Assyrians all knew of an earthly paradise that had once lain beyond the Zagros mountains, beyond what they called the Seven Heavens," he says. "For them, Eden was still very much an earthly place. Only later Judeo-Christian tradition bestowed heavenly status on it."

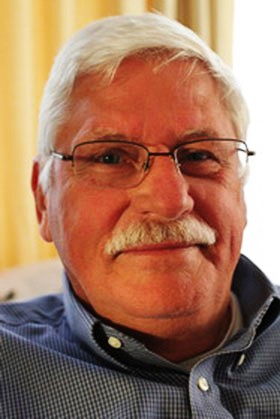

A few years earlier, another Eden-hunter had started his search from the same area, but taken a different direction. In the mid- 1980s, Prof. Juris Zarins, an internationally renowned archaeologist at Southwest Missouri State University in Springfield, placed the Garden of Eden in a prehistoric plain beneath the head of the Persian Gulf, a few hundred miles south of Rohl's location. Zarins, who traveled to the site and also used satellite photography to bolster his claims, identified the enigmatic Gihon and Pishon rivers as the Karun, which begins in Iran and flows south to the Gulf, and a "fossil river" that once flowed through northern Arabia. Around 4000 BCE, Zarins believes, the lush oasis of Eden was submerged beneath the waters of the Gulf as a sudden rise in sea level swallowed prehistoric settlements. Responding to Rohl's new theorizing, a reinvigorated Zarins is now about to set off again for the Gulf, to investigate further.

"Before the so-called Flandrian Transgression," Zarins told The Report, referring to a worldwide rise in sea level between 5000 and 4000 BCE, "the land used to be completely dry all the way to the Strait of Hormuz, and as in the Biblical description, the four rivers seemed to merge into one at what's now the top of the Gulf. The Sumerians always insisted their ancestors had come out of the sea. To them, Eden was not a story; it was the living tradition of their origins."

While Rohl disagrees on the precise location, he readily accepts Zarins' ground-breaking arguments that Eden was more than just a poetic allegory for humanity's loss of innocence. The Genesis story, Zarins argued in a well-received 1987 article in the Smithsonian magazine, is a much-abridged account of the greatest revolution in human history: The transformation of humans from drifting hunter- gatherers to settled, self-reliant farmers.

Between 6000 and 5000 BCE, Zarins believes, bands of foragers, displaced from their drowning Eden, moved up to Mesopotamia only to find themselves face to face with more technically astute agriculturists coming down from the north. The northerners were the Ubaidians, the precursors of Sumerian civilization, and the clash between two lifestyles led to an upheaval in the nomads' customs and values.

Over time, the prehistoric cultural shakeup was word-of-mouthed into the story of the loss of an earthly idyll: by playing God, humans lost their right to natural bounty and condemned themselves, in the Bible's words, to eating from the soil "by the sweat of [their] brow."

The first farmers tried to convert the hunters and gatherers into agriculturists, which caused a great existential crisis," Zarins theorizes. "Their confrontation was so powerful that it became an integral part of the earliest Sumerian stories, and from there it passed into the Hebrew Bible" as the story of hunter Abel's murder by farmer Cain. "But by then, the real events and players had long since vanished into the mists of history, and now the story had to explain why humanity had done away with a wonderful, simplistic lifestyle provided by God's produce or nature's bounty."

* * *

Rohl has no argument with Zarins' talk of an agricultural revolution; he even knows its leader. Adam did live (circa 7000 BCE), Rohl suggests, leaving the world of geographical and geological certainty and entering the realm of speculation. Pointing to numerous ancient legends, Rohl notes that humanity's first known leader was called Adamu in Assyrian, Amuta in Babylonian, Adapa in Sumerian and Atum in Egyptian. His name in Hebrew means "red earth man," argues Rohl, not because he was fashioned from clay but after the red-ocher mountains near Lake Urmia, where Adam was chieftain of the first prehistoric farmers. Prehistoric graves, uncovered in the area, have yielded human skeletons coated in red ocher a "dead giveaway," says Rohl.

"Perhaps Adam was a priest or a shaman," Rohl suggests, "the interface between his tribe and his god. He was the great ancestor of leadership on earth." And Eve? Rohl sees her as a bride to Adam from another settled tribe. Perhaps she was the mother of the founding dynasty of civilization, which included patriarchs known by such Genesis names as Cain, Enoch, Methuselah and Tubal-Cain.

"Genesis is pure history," Rohl enthuses. "It tells us about the hunter-farmer tensions, the Cain-Abel struggle" and now, he notes, DNA testing has shown that, around 10,000 to 5,000 BCE, the first farmers were indeed active there, pioneering the domestication of wild wheat in the Miyandoab plain.

This spring, David Rohl is returning to his fertile plain in northern Iran, not with a jeep and driver, but with TV crews from the BBC and the Discovery Channel. He also intends to begin digging there. "I hope to find traces of Neolithic settlements that take us back to the era of Adam and Eve," he says. Then, in dry deference to his critics, he adds, "I know I'm not going to find the Tree of Knowledge."