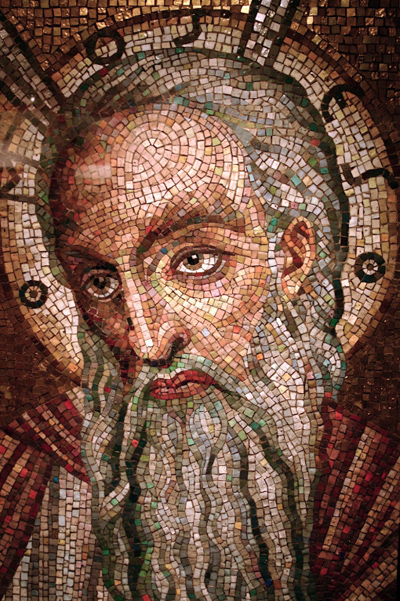

What Would Moses Do?

Rabbi Harold Kushner is back, with more commonsense advice. The bottom line: knowing that we’ve done the right thing should be its own reward

Tibor Krausz

The Jerusalem Report, October 30, 2006

“Behold and see if there be any sorrow like onto my sorrow,” cries the prophet Jeremiah in Lamentations (1:12), speaking for all of us in times of distress.

Help is on the way.

In “Overcoming Life’s Disappointments,” his tenth volume of spiritual guidance, Harold S. Kushner, bestselling author and rabbi emeritus of Temple Israel in Natick, near Boston, attempts to show us the way out of despondency.

We may justifiably be wary of new self-help primers. Such guides already number in the zillions, and routinely they peddle mere commonsense as revolutionary lifestyle advice by coaching platitudes in the pseudoscientific jargon of psychobabble, or by proffering quasi-spiritual bromides in the form of enlighten-yourself instruction manuals. To lend their aphorismatic fare pragmatic credibility, many an author trots out saints and heroes (“Leadership Secrets of Attila the Hun,” “What Would Buddha Do?”) to serve as putatively empirical evidence of a therapy’s worth.

In using Moses for his case study, Kushner, 71, treats on especially treacherous terrain: at the very least, there’s a risk in narcissistically magnifying our everyday failures into Biblical proportions. Yet his articulate, no-nonsense treatise, which reads like serialized Shabbat sermons comprising benign rabbinical commentaries and avuncular tips, carefully sidesteps the pitfalls of advocating emulation by association. We can, Kushner notes, never hope to be Moses. And thank God for that.

Moses’ biography in the Torah hardly makes for an enviable life. Handpicked by God to deliver His chosen from bondage, Moses gets caught between a band of cantankerous recidivists and an increasingly irascible deity. God instructs him; the Israelites ignore him. Moses gives them laws; the Israelites disobey him. He rouses, inspires, and consoles them; they bellyache constantly. For all his efforts, Moses gets no thanks in the end; even God seems to desert him. After 40 years of wandering in the desert, he must die within sight of the Promised Land. In short, he can’t have been a very happy man.

“Moses’ triumphs were spectacular,” Kushner writes, “but his frustrations and disappointments must have been searing.” The greatest prophet, he argues, was a singularly unappreciated man in his lifetime. Hence the power of his example: we should do right by our neighbor not for gratitude and plaudits but simply for the sake of doing the right thing. Moses’ conduct, he argues, embodies the ideal of hesed shel emet, or “true kindness,” that we would all do well to emulate.

* * *

Disappointments result when expectations come up against an uncooperative reality. One way to resolve this dilemma is to renounce all desire, thereby hoping to attain a permanent state of cultivated indifference (Buddhism). Another way is to embrace suffering, regarding life’s tribulations as a necessary test run of the soul before the reward of eternal bliss in the afterlife (Christianity).

Because Judaism is concerned primarily with the here and now, God’s grace is understood to center on our daily life in a world underwritten by a universal code of justice. Yet often, experience flies in the face of a putatively moral universe, and we’re left trying to make sense of our undeserved misfortune. The perennial optimism of Proverbs (“The righteous will flourish like green leaves”; 11:28) gives way to the melancholic fatalism of Ecclesiastes (“[T]he race is not to the swift... neither yet bread to the wise...., but time and chance happeneth to them all”; 9:11).

Kushner, who wrote the perennial bestseller “When Bad Things Happen to Good People” (1979), tries to resolve the paradox. To tackle the corrosive implications of blind chance over the idea of a Just Creation, he parses key liturgical and Biblical passages that indicate whimsical vindictiveness on God’s part until the texts resonate to him of a deeper meaning pointing to divine compassion and benevolence. He advocates an almost Nietzschean view that the soul’s greatness is forged in adversity: in a world without challenge and suffering we’d all turn into hopeless slackers with none of us ever living up to our full potential. (Rationalists/agnostics may dismiss such exegesis as misconceived and sophistic by attributing anthropocentric causes to impersonal forces of nature; yet there’s a tempting humanism in Kushner’s views.)

Taking Moses as his model, he explains how our failures are often blessings in disguise — by goading us on to better ourselves or choose a different path. To wit: No sooner does Moses prohibit idolatry than his wayward followers take to worshipping a golden calf. Enraged, the prophet smashes the tables inscribed with God’s Commandments. Momentarily, however, he’s painstakingly gathering up the stone fragments to preserve them in the Ark of the Covenant alongside an intact replacement set of the Law.

Lesson: When we see our loftiest dreams foiled by circumstance (the Israelites won’t be wholeheartedly righteous, after all), we can, Kushner writes, “trade in [our grand old] dream for... a more realistic one.” Far from succumbing to a sense of inadequacy, we must simply recalibrate our expectations in light of a better understanding of our inherent abilities and prospects.

Even die-hard tenacity doesn’t guarantee success, of course. Yet sanguinity and resilience are their own rewards, he argues. We may fail to surmount our problems, but we can refuse to be dismayed by them. Kushner quotes Viktor Frankl, a Viennese psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor: “Everything can be taken from a man but… the right to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances.”

Moses’ psychological toolkit also comes in handy when dealing with myriad other forms of frustration, Kushner says. He exemplifies his Mosaic how-to tips with myriad contemporary anecdotes from his rabbinical counseling sessions, enlivened with eclectic yet apposite exempla from Golda Meir (about overcoming physical unattractiveness) to Yiddish theatre (about the import of keeping promises) to aphorisms printed on refrigerator magnets (about daring to dream).

It all makes for a readably inspirational homily diffused with subtle humor, even though most of his tips we may well have heard or guessed intuitively before. Still, in communicating time-honored counsel amiably anew with compassion and unfailing optimism, Kushner’s book can serve to fortify us in times of loss and frustration.