The Kaiser’s Jihad

A sweeping account of Germany’s fitful and ill-fated venture to reshape the Middle East in the slide to World War I

Tibor Krausz

The Jerusalem Report, January 31, 2011

More than a century ago, the German diplomat Max von Oppenheim made a startlingly accurate prediction. In a consular dispatch from Cairo to Berlin in 1906, he wrote: “[T]he demographic strength of Islamic lands will one day have a great significance for European states.” He added knowingly: “We must not forget that everything taking place in a Mohammedan country sends waves across the entire world of Islam.”

Kaiser Wilhelm II’s point-man in the Middle East was no idle observer of that trend. He was actively seeking to rekindle Islamic fervor against European colonial powers — not so much out of sympathy for real or imagined Arab grievances as out of cold opportunism. Oppenheim hoped to dislodge Britain from its empire in Asia by grafting German expansionism onto incipient pan-Islamism in order to lay the ideological foundations for Germany’s domination of the region. The Catholic scion of a prominent Jewish banking family (on his father’s side), he cultivated fire-breathing Islamists, penned vitriolic screeds against Britain in Cairo newspapers, and did his best to raise the green banner of jihad.

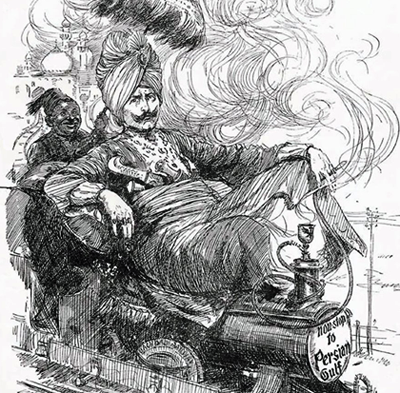

From the summer of 1914 onwards, years before Lawrence of Arabia galloped into view and history books on camelback as a champion of the Arab cause, Oppenheim’s intrepid German jihad agents were fanning out across the Middle East and Central Asia. They were on a mission for Wilhelm, a vain, impetuous, impressionable megalomaniac given to larger-than-life posturing. In his grandiose Weltpolitik, the Kaiser sought to unite Europe and Asia under the stewardship of Imperial Germany. His ambitions were to culminate in a feat of engineering to provide a gateway for Germany into the heart of continental Asia: a railway link between Berlin and Baghdad. Ground for the grand project, which would be financed and engineered entirely by Germany, was broken at Istanbul’s Haydarpasha Station in mid-1906. From there, the line would have to wind its way through 2,000 miles of marshes, deserts, forbidding mountain ranges and the lands of marauding nomads, all the way to Baghdad (then a sleepy backwater) and on to the Persian Gulf.

The story of the Ottoman Empire’s demise and the accompanying shenanigans by European powers that permanently reshaped the Middle East’s political landscape has often been told. Where Sean McMeekin breaks new ground in his informative “The Berlin-Bagdad Express” is demonstrating in minute detail the extent of German efforts to further the cause of newly resurgent radical Islamism in a misguided attempt to enlist it as an ally. He disagrees with historians like David Fromkin, author of the seminal “A Peace to End All Peace,” who have portrayed German attempts to stoke the fire of jihad as peripheral to the country’s strategic plans in the Great War. McMeekin, who teaches at Yale and plumbed formerly unexplored Turkish documents, insists that “Germany’s leaders saw in Islam the secret weapon which would decide the world war.”

At the heart of that policy stood the German emperor, the heir to chancellor Otto von Bismarck’s unified and increasingly belligerent Germany. In McMeekin’s account, Wilhelm comes across as a bumbling (no surprise there) yet ultimately sinister figure whose impulsive politicking would have lasting consequences for the Middle East. A grandstanding romantic and an avid Orientalist, Wilhelm strove to reshape a region coming undone at the seams after centuries of Ottoman rule. He had taken a leaf out of Russia’s playbook for a bold thrust into Central Asia during the Great Game.

“Whereas Hitler [would be] willing to concede the British their global, sea-based empire in recognition of his own domination of the Eurasian landmass,” McMeekin writes, “Wilhelm wanted the British empire too, including its crown jewels of Egypt and India.” Britain ruled over more than 100 million Muslims, and the Kaiser hoped to undo its empire by fomenting dissent among their ranks. He befriended the volatile Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid II by promising him German protection against Russia and Britain. Enamored of the Muslim faith, the German emperor then restyled himself “Hajji Wilhelm,” the benevolent protector of Islam — not necessarily to the delight of all the officials at the German Foreign Office on Wilhelmstrasse, several of whom remained wary of the Kaiser’s mercurial exploits.

* * *

Wilhelm found his intrepid envoy to the Arab world in Oppenheim, whose fortune from his family’s banking dynasty allowed him, McMeekin writes, to “moonlight alternately as explorer, writer, diplomat, archaeologist and prospector.” An unscrupulous operator, Oppenheim came into his own first as a German consular representative in Cairo, then as head of Germany’s Intelligence Bureau for the East in Berlin — “the jihad bureau,” as McMeekin calls it — during the war. A self-styled “Baron” who was “almost preternaturally favorable to all things Arab,” Oppenheim began planning a global jihad “with Germans and Muslims fighting together, shoulder to shoulder,” in his own words.

Accordingly, his agents began bribing Muslim jurists, from Mecca to Kabul, into issuing specially designed fatwa rulings. The German-sponsored holy war was to be launched selectively: “against all Europeans, with the exceptions of Austrians, Hungarians, and Germans” (i.e. Central Powers nationalities). By war’s end Germany was to have spent a colossal 3 billion marks in all on its jihad effort.

The Young Turk Revolution of 1908, which unseated Wilhelm’s friend the sultan popularly known as “Abdul the Damned,” had caused a hiccough to German designs. Yet Wilhelmstrasse soon found a new ally in the Young Turk government’s ambitious Minister of War Ismail Enver. Like the sultan before him, “Enver Pasha,” who waxed his mustache in the perky style of Wilhelm’s trademark whiskers, came to rely on German military might and prowess in his bid to revive Turkey’s fading fortunes. He proved himself a willing accomplice for Oppenheim’s jihadist agitation.

The rapid unraveling of the Ottoman Empire in the early 20th century became a rallying cry for Muslims worldwide (just as the loss of “Palestine” to the Jewish state would in later decades), which was a godsend to German propaganda. Oppenheim’s jihad bureau was busy concocting stories of Britain’s anti-Muslim perfidy. Throughout much of the Ottoman Empire, German-sponsored jihadist pamphlets — in Arabic, Farsi and Urdu — were stirring up age-old ethnic and religious resentments, triggering flare-ups of violence against local Christians. “The blood of the infidels in the Islamic lands may be shed with impunity,” Oppenheim demanded bombastically, citing the scriptural authority of the Koran to “slay [the unbelievers] wherever ye find them.” “The Kaiser’s desire,” in the laconic words of a German official, was “to let loose 300 million Mohammedans in a gigantic St. Bartholomew’s massacre of Christians.”

German propaganda helped pioneer the modern phenomenon of harnessing the time-honored doctrine of jihad to the cause of indiscriminate bloodshed. In a chilling precursor to al Qaeda, Oppenheim called for a “jihad by bands,” whereby pious Muslims formed localized terror cells in India, Central Asia, and Egypt to assassinate nationals of the Entente Powers (the British, French and Russian alliance which stood against the German-led Central Powers).

Then as now, tragedy and farce went hand in hand. Oppenheim recruited Francophone Muslims from German prison camps to be designated as the ostensible vanguard of an army of North African holy warriors. The hapless POWs travelled to Istanbul on the Orient Express registered as “acrobats” of an itinerant circus. Once a jihad was proudly declared from the balcony of the German embassy in Istanbul’s European colony, the newly anointed holy warriors set about looting and torching English- and French-owned shops along with a locally recruited mob. “The German jihad was up and running,” McMeekin notes wryly.

* * *

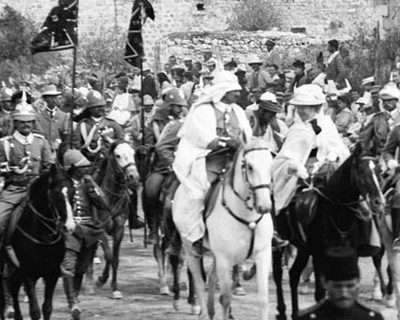

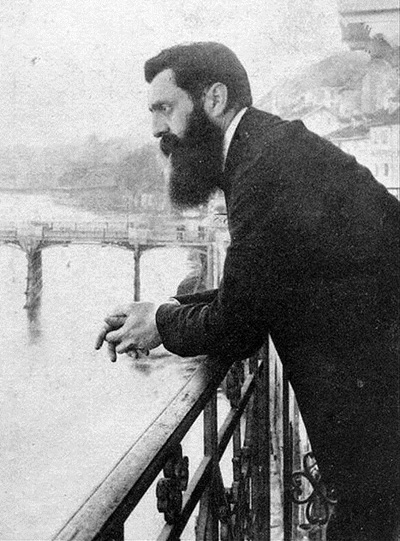

Ironically, just as Kaiser Wilhelm was busy wooing Muslims, he also established rapport with the Zionists. During his visit to Istanbul in November 1889, Wilhelm met Theodor Herzl, who converted him to the Zionist cause. On a subsequent tour of the Levant in 1898, Wilhelm rode into Jerusalem in style as a conqueror, bedecked in a Prussian field marshal’s uniform astride a black charger. In the city he reiterated his support to Herzl for German Jewish colonization of Ottoman Palestine, just before the first international Zionist Congress in Basel later that month. “Your movement,” Wilhelm told Herzl, “is based on a sound, healthy idea. There is room here for everyone.”

Germany would go on to nurture the budding Zionist movement, which had been incubating in the country’s political and cultural milieu and that of Austria-Hungary. During the war most German Zionists, McMeekin observes, were “strong supporters of the Hohenzollern throne, especially after Germany joined battle with Tsarist Russia, universally regarded as the greatest enemy of world Jewry.” Some of them even envisioned their cousins in Russia crippling the tsar’s war effort through insurrection. This plan ignored the patriotism of many Russian Jews, as many as 400,000 of whom were serving in the Russian army, although mostly as conscripts, at the beginning of the war.

In return for widespread Jewish support, the Germans even leaned on their Turkish ally to declare Palestinian Jews “a good and loyal element,” in a 1915 proclamation by the Porte. Germany’s ostensible concern for Palestinian Jewry wasn’t purely altruistic. The government supported the Zionist endeavor in the hope that German Jews would emigrate to Palestine en masse, thus vacating the fatherland. “Of course, later it would also occur to the Nazis, who actively encouraged Jewish immigration to Palestine in the late 1930s and did not really abandon the idea until 1941,” McMeekin writes.

Yet German support for the Zionist cause did prove valuable, not least because it prompted Britain to begin paying lip service to Zionist aspirations, even while it, too, was doing its best to stir up Arab nationalism. “The most astonishing thing about the Balfour Declaration is not that the British tried so blatantly to win over world Jewish opinion, but that they did so in a fit of pique against the Germans,” McMeekin writes.

Not that there were no honest brokers for Zionism among the British. Despite his vaunted credentials as English Arabism’s celebrated grandee, Lawrence of Arabia was one. The British Jewish historian Sir Martin Gilbert recently pointed out that in 1921, soon after his famous exploits, the English colonel was trying to sell Churchill, then Colonial Secretary, on the idea of a “Jewish state from the Mediterranean shore to the River Jordan.” Lawrence, Gilbert said, “had a sort of contempt for the Arabs [and] felt that only with a Jewish state would the Arabs make anything of themselves.”

The colonel was hardly alone in waxing ambivalent about Arab allies. “Unlike Lawrence, [German] field agents,” McMeekin writes, “were fluent enough in Arabic to understand Bedouin culture as it existed on the plane of reality, rather than in romantic Oxbridge imagination.” The plucky Germans — like archaeologist and secret agent Hans Lührs who operated among the tribes of Mesopotamia — often learned the hard way that the desert warrior’s code wasn’t adverse to mendacity and deceit. The Middle East’s topsy-turvy world of divided loyalties, broken promises, internecine vendettas and chronic dissembling gave the Germans a crash course in regional politics.

By 1916, when the fortunes of war were favoring the Entente Powers, Arab tribesmen began turning on their German allies, robbing them blind, selling them out to the British, and murdering them outright. Meanwhile, Oppenheim’s jihad bureau also began unraveling — often in comical circumstances. A leading jihadist firebrand writing for the Turkish press, one “Mehmed Zeki Bey,” for instance, turned out to be “a Romanian Jewish conman who had recently done a turn running a bordello in Buenos Aires,” McMeekin says.

* * *

Although at times it feels scattershot and disjointed, McMeekin’s sweeping, well-researched account deserves to become a benchmark in scholarship about the Kaiser’s fitful and ill-fated venture to reshape the Middle East. It’s an unsung yet important story, and the historian does credit to it.

For better or worse, Germany’s earnest if half-baked efforts during WWI have left an indelible mark on the region. For one thing, German engineers laid down what still forms “the backbone of the railway systems of modern Turkey, Syria, Jordan, northern Arabia and even a good deal of Israel and Palestine,” McMeekin points out. Less happily, the Kaiser’s dogged agitation for jihad helped sow the seeds of the enduring religious fanaticism that continues to blight the world today.

Needless to say, neither the Kaiser nor Oppenheim had any regrets in hindsight. Wilhelm, the erstwhile Zionist sympathizer, began blaming Germany’s defeat in the war on — who else? — the Jews. Presaging Hitler, in a letter dated December 2, 1919, Wilhelm extolled his compatriots not to “rest until these parasites have been wiped out from German soil and exterminated.”

As for Oppenheim, the progeny of Jews gladly embraced the status of “honorary Aryan” the Nazi regime bestowed on him, along with the decoration for his services in fomenting jihad against the fatherland’s enemies. On July 1940, Oppenheim, zealous as ever, produced a new “Memorandum on the Revolutionizing of the Middle East.” He had by then become a close friend of the rabidly anti-Semitic grand mufti of Jerusalem, Mohammed Amin al-Husseini, who had distinguished himself by orchestrating lynch mobs against Palestinian Jews. McMeekin posits that the mufti had drawn inspiration from Oppenheim’s onetime jihad fatwas for his own against Jews and Brits, including his notorious ruling in 1948 which sanctified the murder of Israelis as a Muslim duty in perpetuity.

“In the Baron’s self-pitying rejection of his Judaic heritage,” McMeekin notes, “we can see at work that virulent syndrome of bourgeois self-loathing so common in the modern west.”

And so Oppenheim’s political legacy lives on — not only in the homicidal religious militancy he worked so hard to unleash but also in a prevalent form of benighted cultural relativism that blinds itself to the implacable hostility of Islamism to western civilization. It was quite a life's work for a wealthy dilettante in the service of a narcissistic fool.