The Ark Continent

Yet another hopeful searcher locates the famous Biblical cultic object in Africa

Tibor Krausz

The Jerusalem Report, June 10, 2008

Joshua conquers the Promised Land with its help. David consecrates Jerusalem by its presence. Solomon builds a temple for it. Then after the Babylonians sack Jerusalem in 587 BCE, “the Ark of [the Lord’s] strength” (Psalm 132) vanishes. The Bible says not a word about how and where.

Rabbis, scholars and laymen have been wondering ever since. Maimonides believed the Ark had been hidden in a secret subterranean chamber on the Temple Mount. The apocryphal Second Book of Maccabees reports that it was placed by the prophet Jeremiah in Moses’ burial cave at Mount Nebo (in today’s Jordan). Muslim tradition had it that the Ark was laid beneath the Kaaba in Mecca. Yet others “located” the lost relic in the Judean hills, underneath the Sphinx, or underwater in Lake Kinneret. In other words, no one had a clue.

Tudor Parfitt thinks he finally does. Two decades ago he set out to track down the elusive relic, or what’s left of it. “The revelation of what he found will rewrite history” promises the blurb for Parfitt’s account of his discovery, “The Lost Ark of the Covenant.”

There’s nary a peddler of New Age “archaeology” worth his salt who doesn’t advance the same modest claim. But Parfitt is no “wisdom of Atlantis” kook. He’s professor of Modern Jewish Studies at the University of London, a fellow at Harvard’s Du Bois Institute for African and African American Research, and author of several well-received books on subjects ranging from Lost Tribe myths to Jewish-Muslim relations. No armchair boffin, Parfitt, dubbed “a British Indiana Jones” by The Wall Street Journal, has made a career out of visiting self-proclaimed Lost Tribes the world over, most recently in Papua New Guinea.

Where better to find the long-lost Ark than in the possession of a Lost Tribe? In Parfitt's view, the “Lost Tribe” is the Lemba and the Ark is their ngoma lungundu — a wooden drum used for storing sacred artifacts. Carried aloft on two poles, the Lemba’s ancestors bore it as a palladium into battle where the relic blasted enemies with a mysterious “fire of God.” Only members of the priestly Buba clan could handle it, Parfitt says, and again like the Ark it was never allowed to touch the ground. Local tradition claims the ngoma came from Solomon's Temple.

Last year, Parfitt says, he discovered the object, missing for a half century, gathering dust in a storage room of a museum in Zimbabwe.

* * *

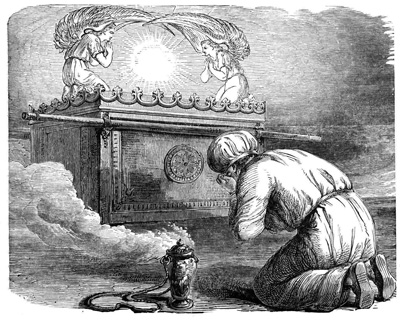

As many famous Biblical tales, the popular story of the Ark is a composite of disparate accounts. According to Exodus, the Ark of the Covenant was crafted by the artisan Bezalel, working from a divine blueprint. His masterpiece is overlaid with gold inside and out; it's capped with the “mercy seat,” a golden lid decorated with two guardian cherubim mounted on top to serve as God’s earthly throne. The Ark was carried on poles inserted into four gold rings at its corners. Deuteronomy, meanwhile, describes the Ark (aron ha-brit in Hebrew; literally the “covenant chest”) as a plain shittim, or acacia-wood, coffer fashioned by Moses at Mount Sinai to contain the Tablets of the Law.

The Ark of Exodus is dangerous magic. It allows Moses to commune with God and strikes dead any injudicious Israelite who nears or touches it. (Pondering this curious feature, Swiss Ufologist Erich von Daniken proposed that the Ark was an electrically charged transmitter used by godlike space aliens to beam messages down to Moses. Why the bossy extraterrestrials didn’t use walkie-talkies von Daniken didn’t say.) During the conquest of the Promised Land, the Ark parts the River Jordan and brings down the walls of Jericho. When invading Philistines capture it in battle, they’re struck by hemorrhaging boils (1 Samuel). Even Israelite priests can approach it only in the protective cloud of incense. Yet it also gives life, bringing forth foliage and fruit in Solomon’s Temple.

Were there two Arks then? Or even more? Biblical narratives (in Kings and Chronicles) hint that several versions of the Ark may have been kept at various locations before the cult of Yahweh was centralized in Jerusalem. That begs other questions: Did the Ark of the Covenant exist in the first place? And if so, what sort of Ark was it?

The Platonic Jewish philosopher Philo of Alexandria saw the Ark’s dimensions — 2.5 cubits long, 1.5 cubits wide and high (3ft by 2ft by 2ft) -- as encoding the archetypal ideals of Creation in numerical descriptions of divine harmony decodable with Pythagorean precision. Similar speculations would fire medieval mystics, kabbalists and freemasons. A rival rabbinic tradition suggested that the Ark of the Covenant had become the heart of every Jew who loves God and abides by His Law. A Christian belief in turn co-opted the sacred relic into the cult of the Virgin Mary, announcing Jesus’ mother to be the new Ark of the Covenant as the flesh-and-blood bearer of the Word of God.

Ask skeptics, though, and the Ark of the Covenant no more plausibly existed than did Noah’s Ark. An urban legend of antiquity, it was not an object but an idea. The mythical Ark served as a potent symbol for the ineffable nature of the shekhinah. In its specific details, the Ark was likely modeled after such prototypes as Egyptian funerary chests (like the one found in the tomb of the pharaoh Tutankhamen) or Assyrian coffers. Myriad ancient cultures also depicted their gods flanked by winged mythic creatures, as the God of Israel was believed to reside on the Ark’s “mercy seat,” except He was invisible.

For many Ark enthusiasts, however, not only did the Ark exist; it still does — in Aksum, in northern Ethiopia. In his best-selling “The Sign and the Seal” (1992), journalist Graham Hancock speculates that the Ark of Moses has been kept hidden from view in the church of St. Mary of Zion, where idiosyncratic Christian traditions still celebrate the relic in song and ritual.

Parfitt travels to Ethiopia, rules out the local ark as a Christian altar box, and puts his money on the Lemba.

* * *

The Bantu-speaking Lemba, whose 40,000 members live in Zimbabwe and South Africa, claim descent from ancient Israelites. The black Africans, whose clan names appear Semitic in origin, Parfitt claims, call themselves Muzungu ano-ku bva Senna — “the white men who came from Senna.” Senna is the lost city that, lore has it, their ancestors established after leaving Jerusalem with the Ark of the Covenant. Parfitt traces the town to northeastern Yemen, where in the pre-Islamic 6th century a short-lived Jewish kingdom flourished after a local warlord embraced Judaism.

The Lemba gained worldwide fame as the “Black Jews of Southern Africa” in 1999, when half of Buba males, their priestly clan, were discovered to have the same genetic marker as Cohanim, suggesting common ancestry with Jerusalem Temple priests. A decade before, it was Parfitt himself who had “outed” the Lemba as a “lost tribe.”

Following his pioneering fieldwork with the African tribe in the late 1980s, Parfitt’s scholarly interest in the Ark grew into the full-blown obsession of a treasure hunter. In his account of his search, the Judeophile Welshman, 63, who studied Hebrew at Oxford and lived in Israel in the early 1990s, shows a novelist’s eye for anecdote and suspense. Complementing archival research with old-fashioned sleuthing in the field (often egged on and accompanied by a wealthy and flamboyant “born-again” Orthodox Jewish friend hoping to pacify the Middle East through the power of a restored Ark), Parfitt travels hither and yon to untangle myriad “leads” — ancient, medieval, modern.

“The Lost Ark” reads like a zippy travelogue as Parfitt's (generally quixotic) quest takes him from Jerusalem to Oxford to Zimbabwe and beyond. Braving his fear of snakes, he even visits the “Jews of Fly Swamp” in Papua New Guinea — erstwhile cannibals who claim to have the Ark (their sacred “fire pot”) with Aaron’s rod, sunken in a crocodile-infested boggy lagoon. They welcome him excitedly as a prophesized messianic figure who will lead them to Israel. “I felt like a visiting deity,” the scholar writes. “Except I was wearing baggy cotton trousers and no socks.”

As sound scholarship, though, Parfitt’s book is less impressive. At times he offers already familiar theories (detailed in works like “The Ark of the Covenant,” 1999, by Roderick Grierson and Stuart Munro-Hay) repackaged as hard-earned new insight, but provides no bibliography or notes. Parfitt also drops the occasional howler. “I stood in the shade of the pyramids,” he writes about an expedition to Egypt, “the Hebrews had helped construct.”

They had? The pyramids of Giza were built in 2500 BCE during Egypt’s Fourth Dynasty, whereas the Egyptian Captivity is dated (both in the Biblical chronology and by scholarly guesstimates) to a millennium later. A popular Jewish belief notwithstanding, no Hebrews could have built the pyramids short of time travel. Likewise, in the vein of similar Grail quests, Parfitt’s hunches are backed up by speculations which are then supported by folklore and hearsay. Identifying the Lemba’s ngoma as the Ark requires quite a leap of faith — not least because the ngoma looks nothing like the Biblical Ark. It looks like, well, a common African hard-wood drum.

Desperately combing the Lemba’s craggy homeland for the ngoma, said to be guarded by 12 lions and a two-headed serpent, he finally locates it — in a bit of a comedown — as item Q.V.M. 5218 in the Museum of Human Sciences in Harare. There the object (labeled as a “drum”) remains stored on a bottom shelf in a dusty storeroom. Half of one side of it is gone, Parfitt reports, and its remaining lid is covered in burn marks. It isn’t covered in gold and when Parfitt and a curator touch “the Ark,” it doesn’t strike them dead. Then again, the curator’s hand starts bleeding “all by itself.”

So is this the lost Ark? Parfitt has no doubts. He lists Lemba oral traditions that insist the ngoma manifested the same magical attributes and required the same reverence as the Biblical Ark

.

Other scholars won’t be so sure. Last October a radiocarbon analysis performed by archaeologists at Oxford University on a fragment from the artifact found the ngoma to date from the mid-14th century CE. Parfitt argues that his find is a later replica of a truly ancient object. “There can be little doubt,” he asserts, that the ngoma “is the last thing on earth from direct descent from the Ark of the Covenant.”

A Lemba professor, too, assures the scholar: “The whole world will celebrate because they will see the Lemba as the, what d’you call, guardians of the Ark.”