Tales of a Tortured Town

In Jerusalem’s history holiness routinely went hand in hand with homicide

Tibor Krausz

The Jerusalem Report, September 26, 2011

At the end of his pilgrimage to Jerusalem in 1267, the Biblical scholar and commentator Nachmanides, also known as the Ramban, found, to his horror, a ramshackle town of tumbledown dwellings with just two Jewish residents. “Oh Jerusalem,” he lamented, rending his clothes, “I wept bitterly.”

Two centuries later a similar sight awaited another pilgrim, Rabbi Obadiah di Bertinoro. “The poorest Jews,” he noted, “live in heaps of rubbish, for the law is that a Jew may not rebuild his ruined home.”

Another few centuries, and the state of affairs was much the same. If a Muslim set upon a Jew, a European visitor reported in 1766, “the Jew goes away cowering.” Jews still lived in squalor and were still banned from repairing their houses.

Come the early 20th century, the storied city of David and Solomon was still not much to write home about. During a two-week tour of the Holy Land in 1918, the Zionist leader Chaim Weizmann found the Jewish part of the Old City to be “a miserable ghetto, derelict and without dignity.” He refused even to spend the night in the town.

For most of its long history, Jerusalem, that venerated object of millennial Jewish longing, was not a happy place for Jews. Often it wasn’t much fun to be Christian or Muslim there, either.

Over the past 3,000 years, Jerusalem has been conquered almost 40 times, destroyed 18 times, and repopulated endlessly. For most of the past two millennia Jews were a powerless, disenfranchised and disdained minority struggling to retain a toehold in their ancestral capital. If they were lucky, they were allowed to remain on sufferance so that their downtrodden status would serve as a reminder of their ostensible fall from grace. If they were less lucky, they faced periodic expulsions, lynching and massacres.

Each new ruler — Romans, Byzantines, Persians, Arabs, Catholics, Ottomans — set about stamping their marks on the city’s spiritual landscape while trying to erase those of their predecessors. As a result, perhaps the best way to think of Jerusalem is not as a single city but as a series of cities that grew up over time, one succeeding the other, around a single focus that anchored divine purpose to tangible mundane geography: the Temple Mount.

In vying for supremacy over the Holy City, rival religious traditions often wantonly appropriated the holy sites of the others. A Crusader church on Mount Zion became David’s Tomb. A Templar baptistery was co-opted into service by Muslims as the Dome of Ascension, where Mohammad was said to have ascended to heaven on his Night Journey on his steed Buraq. Nearby on the Rock, a natural groove on the boulder that was formerly attributed to a footprint of Jesus was reinvented as Buraq’s hoofprint.

And so the back-and-forth went. After their capture of the city from war-weary Byzantine Christians in 638, the Muslim conquerors walled up the Golden Gate to thwart Jewish prophecy, which foresaw the Messiah entering there. In a bid to outdo the Christians’ Church of the Holy Sepulcher, they erected the Dome of the Rock, which still dominates the city’s skyline. They did that at the very site where they believed the two Jewish temples to have once stood and which Christians before them had used as a garbage dump to mock Jews. Not to be outdone in religious triumphalism, after their own conquest of the city in the 12th century, the Crusaders turned the Muslim shrine into their Templum Domini (Temple of Our Lord) with a crucifix mounted on top until Saladin recaptured Jerusalem in 1187 and cleansed the Temple Mount with bucketfuls of rosewater from Damascus.

* * *

“Jerusalem’s gift for dynamic reinvention and cultural theft is endless,” notes Simon Sebag Montefiore in his engaging and highly informative history, “Jerusalem: The Biography.” “Sacred geography,” adds James Carroll in his own new book on the city, “Jerusalem, Jerusalem,” “create[d] battlefields.”

Montefiore, who is best known for his books on Stalin, is a grand-nephew of the famous 19th century British Jewish philanthropist, Sir Moses, who has a suburb named after him, Yemin Moshe (formerly the Montefiore Quarter, where he pioneered the resettlement of Jews outside the Old City’s walls) and whose signet ring with the word “Jerusalem” on it the author now wears. The book comes alive especially in the latter parts where the historian draws on such primary sources as the meticulously kept diary of the bon vivant oud-playing Arab Jerusalemite Wasif Jawhariyyeh, who chronicled life in the city from the turn of the 20th century right up to the Six Day War.

Israel’s capture of East Jerusalem in 1967 is also the last landmark event in Montefiore’s no-nonsense chronological retelling of Jerusalem’s torturous history with each chapter devoted to a new phase in the city’s topsy-turvy affairs. His well-researched and even-handed treatment of the subject needs to be read by anyone who wishes to voice an informed opinion about the historical backdrop for Jerusalem’s seemingly intractable religious and political conundrums.

Carroll, a former American Catholic priest and author of “Constantine’s Sword,” a seminal study on historical Christian anti-Semitism, explores Jerusalem’s spiritual dimensions through its pivotal role in Jewish, Christian and Islamic thought. He portrays Jerusalem as humanity’s ground zero of sacred violence — “violence carried out in this world in the name of another world” — from prehistoric human sacrifices at Mount Moriah (later associated with the Temple Mount) to today’s Palestinian suicide bombers who seek to reach Paradise by murdering Jewish bystanders.

Despite the potentials of that premise, Carroll’s book is a letdown. In his meandering and often abstruse meditation on the city, the author rewards us with such Gnostic-like nuggets of wisdom as “Jerusalem is the womb of self-surpassing . . . the school that teaches knowledge to know itself.”

* * *

In Biblical times, Jerusalem’s holiness as the earthly seat of Yahweh did not just evolve organically. It was scrupulously cultivated by the ruling elite and the local priesthood, a fact both historians pass over in silence. Biblical scholars speculate that it was the priestly author or authors of sections of the Torah who turned Jerusalem into a centerpiece of Jewish worship in order to grant god-given legitimacy to the city’s hereditary priesthood centuries after the time of David. They did so by retroactively glorifying the capital of Judah as the only legitimate locus of an increasingly centralized cult of Yahweh.

Geographically, King David’s decision to make Jerusalem his capital may seem puzzling. The city was relatively far from the coast, isolated from trade routes, and set in agriculturally infertile terrain. Yet the town was also watered by the Gihon spring, and its hilltop location provided it with a formidable natural defense. Then there was the Jebusite citadel’s presumed holiness, which by David’s time was well established.

Yet despite its exalted place in religious history, the actual City of David was no metropolis. According to archeological finds, it probably covered a mere 15 acres at a site which had been occupied already 2,000 years before that. Four-millennia-old Egyptian potsherds mention Ur Salim, a town named after the god of the Evening Star. In 1350BCE, one Abdi-Hepa, the chieftain of a settlement at the site called Beit Shulmani, or House of Wellbeing, is on record beseeching Pharaoh Akhenaten for help against marauding outlaws.

The Bible first mentions the city in Genesis 7:1, when Abraham enjoys the hospitality of Melchizedek, the king of Salem and a priest of the High God, in the land of Moriah. Abraham soon returns, ready to offer his son Isaac as a sacrifice on Mount Moriah, in a test of faith, to God at the very spot where, tradition has it, the Holy of Holies of Solomon’s Temple would stand.

Ceaseless religious strife and unrelenting folly between Jews, Christians and Muslims would come to center around the site’s misshapen Foundation Stone, where, the faithful believe, Adam was created, the Ark of the Covenant stood, Mohammad ascended to heaven, and the world would come to an end on Judgment Day. Throughout the ages worshippers would flock to Jerusalem to die and be buried in a growing necropolis near the ancient rock with an eye to the resurrection of the dead at the End of Times.

Above ground, meanwhile, life was rarely a picnic — not even during times of alleged bliss. For centuries afterwards, Jewish commentators, starting with the 2nd century BCE author ben Sirach, would wax lyrical about the reign of the 3rd century BCE high priest Simon the Just. Montefiore sets the record straight on that. Simon may have been just, but he ruled with puritanical zeal. His observances would have gladdened the hearts of Taliban mullahs. All manner of minor religious transgressions carried the death penalty: wayward Jerusalemites were burned, beheaded, stoned or strangled to death, depending on the nature of their crimes. Four times a day, seven silver trumpets called the faithful to prostrate themselves in the Temple, foreshadowing later Muslim practice.

In another of the many ironies in Jerusalem’s history, the city reached its zenith (before the modern era) under the late 1st century BCE rule of King Herod, a talented, tormented yet much-maligned man whom his Jewish subjects despised and Christians would later come to loath. Herod, a half-Arab convert to Judaism (who we learn dyed his hair), could be homicidally paranoid one day and high-minded the next. Yet he was a relatively benevolent ruler by the standards of the era, Montefiore stresses. During a famine Herod bought grain from Egypt with his own gold to feed starving Judeans. Rich and well-connected, he proved himself a latter-day Solomon by turning Jerusalem into a glorious city with a population of between 70,000 and 100,000. Herod’s Temple, which replaced Zerubbabel’s modest 6th century BCE structure, was a marvel of the ancient world.

It would stand for only as long as it had taken to complete: a mere half century.

* * *

Throughout the ages the fortunes of Jerusalem rose and fell with the vagaries of power politics. The city lay in a region that was a perennial hub of regional and cross-continental conquests — “the cockpit of empire,” as Jesus scholar John Dominic Crossan put it. And if not that, then it was its sacredness that brought attention to it.

Unlike more sanitized accounts, Montefiore spares us no details of the rampant slaughter that routinely went on in the Holy City in times of war. Apropos the Second Temple’s destruction in July 70CE, the historian writes: “The cruelties inflicted by the Romans and the rebels within the walls compare with some of the worst atrocities of the twentieth century.”

Citing the Romanized Jewish historian Josephus’ work, Montefiore relates how thousands of men, women and children were butchered and crucified by the Roman legions and their Syrian auxiliaries, who disemboweled many of them in a search for swallowed treasures. While the Second Temple burned, priests, officiating to the last, were cut down at the altar. Yet some of the city’s factious Jewish defenders were no better: they terrorized, tortured and murdered fellow Jerusalemites with wanton abandon.

In 130 CE, following another failed Jewish rebellion against Rome, a Roman consul reported that “985 villages were razed to the ground [and] 585,000 were killed.” “So many Jews were enslaved,” Montefiore adds, “that at the Hebron slave market they fetched less than a horse.” The emperor Hadrian decided to erase the very memory of Jerusalem by renaming the city Aelia Capitolina and rebuilding it as a Greco-Roman polis with the Temple of Jupiter and his own equestrian statue atop the Temple Mount. He also wiped Judea off the map, renaming it Palaestina.

At times mayhem was interspersed with comedy. During their siege of the city in 1099, sanctimonious Crusaders saw it prudent to please God by reenacting Joshua’s capture of Jericho by marching barefoot around the fortified walls of Jerusalem bearing holy relics and blowing trumpets as Muslim and Jewish defenders taunted them from the ramparts.

Then just as Joshua did with the defenders of Jericho, the Crusaders set about slaughtering Jerusalem’s inhabitants. “Piles of heads, hands and feet [lay everywhere],” a contemporary European account recalled approvingly. “In the Temple of Solomon they rode in blood up to their knees and bridle reins.” Jews were burned alive in their synagogues and 10,000 people were butchered on the Temple Mount. Yet again the sacred site turned into a zealot’s abattoir. Their work done, the warriors of Christ dropped to their knees and offered their thanks to heaven.

* * *

The first man who envisioned a heavenly Jerusalem as an ideal for the mundane, blood-soaked variety was the Prophet Isaiah. His mystical ideas would inspire rich apocalyptic traditions in Judaism, Christianity and Islam alike. Yet Biblical Jerusalem’s transformation into full-blown Holy City took final shape far afield from it: in Babylon. There by its rivers the Jewish exiles “wept when we remembered Zion” (Psalm 137).

That set a precedent for Jews ahead of a far more enduring exile. The Second Temple’s destruction thrust Jerusalem again into the forefront of liturgy and ritual. Shabbat observance in the Diaspora would turn into a ritualistic reenactment of idealized Temple worship. Cups of wine replaced burnt offerings and steadfast observance of the mitzvot replaced animal sacrifice as a way to God. Jerusalem went into exile with the Jews. In medieval Polish shtetls, Carroll notes, rabbis prayed for clement weather for the city. A heavenly Jerusalem, which by God’s grace would one day be restored to earth, became “a designated center of hope,” he says.

Not incidentally, the staunchly secular Zionist movement, whose ideas were more influenced by socialism than theology, would take its own name from the city, Carroll points out. The very notion of homecoming became equated with a return (ascent or aliya) to Jerusalem, “the City on the Hill.”

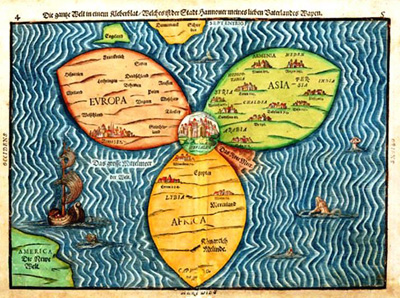

Jerusalem also exerted a great mystical influence over another set of believers who were physically barred from it: Christians. After the debacles of the Crusades, European Christians came to see Jerusalem as God’s Kingdom manifested on earth, the dead centre of Christian cosmogony, the very gateway to Heaven. On medieval maps the city was portrayed as “the navel of the world” and the further away a place lay from it, the more it shriveled into insignificance -- hence the skewed perspective that aligned Europe right into Jerusalem’s orbit. “[C]artography in the west,” Carroll writes, “came into being in part to valorize Jerusalem.”

The city’s own sacred geography would, too, inspire centuries of millennial fantasies. In Jerusalem even the quotidian rhythms of daily life were believed to assume a holy sheen: apotheosis came from the believer’s mere presence in the city. Being in Jerusalem was to have a foot in heaven, yet time and again holier-than-thou posturing led to sectarian strife and sparked internecine violence.

At one point as many as eight Christian sects competed for control over the Church of the Holy Sepulcher with priests coming to blows over such weighty matters as who could sweep the floor where. In 1834 during a riotous stampede in the church 400 pilgrims were trampled to death. A decade later a fight between Catholic and Greek Orthodox priests left 40 of them dead. Frequently, “the crimes of the past returned to haunt the heirs of the future,” Montefiore observes.

Meanwhile, pilgrimage to the city became a cottage industry with venal Jerusalemites milking pious and gullible visitors through tolls, fees and a flourishing trade in phony relics. The pioneering British travel agent Thomas Cook also set up shop, peddling extravagantly conceived package deals. Some more erotically inclined pilgrims made a habit of sealing their unions in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in the belief that children conceived there would be blessed.

By the early 19th century much of Europe and America was in the grip of evangelical fervor for the Second Coming, which would be precipitated by the ingathering of “exiled” Jews to Jerusalem. Almost overnight, Montefiore writes, Jerusalem went from “a benighted ruin ruled by a shabby pasha in a tawdry seraglio to a city with a surfeit of gold-braided and bejeweled dignitaries.” Rich foreign missionaries bought up large swaths of land, the better to convert newly arrived Russian and Yemenite Jews on behalf of the London Jewish Society, a Christian Zionist organization. Herman Melville called it a “preposterous Jew mania.”

In the 19th century alone, Montefiore notes, well over 5,000 books were published in English about Jerusalem. They were either feverish evangelical treatises or scornful travelogues by the likes of Melville, William Makepeace Thackeray, Mark Twain and Karl Marx, who all mocked the squalor of the city and the pious vulgarity of its inhabitants. Jerusalem’s Jews, Thackeray wrote, lived in the “stinking ruins of the Jewish Quarter, venerable in filth,” where they lamented “the lost glory of their city.”

* * *

By the 1890s, Jews were already a clear majority in the city, numbering 25,000 souls in nine suburbs of their own, including the Orthodox neighborhood of Mea Shearim. Yet they continued to suffer repeated harassment and at times murder at the hands of Muslims and Christians as the Ottoman authorities looked the other way, Montefiore says.

His book is a welcome corrective to a prevalent view, popularized by Karen Armstrong’s “Jerusalem: One City, Three Faiths” (1997) and in part by Carroll himself now, which portrays the city’s Muslim rulers as invariably benign. According to that view, it was modern Zionism that hardened Arab hearts against Jews in the Holy Land.

While it may be true that Muslims were often more lenient than Christians, that isn’t saying much considering the latter’s murderous loathing of Jews. After his capture of Jerusalem from Byzantine Christians in the 7th century, Caliph Omar allowed Jews back onto the Temple Mount to pray and he even appointed a Jew as governor. Yet Muslim tolerance wouldn’t last. In 720 the caliph’s namesake Omar II banned Jews from the site again. During the long centuries of Islamic rule Jews now enjoyed tolerance, now faced vicious persecution. Mamluk sultans, who ruled the city from the mid-13th to the early 16th century, required Jews to wear yellow turbans (and Christians blue), even as they let the city go to rot.

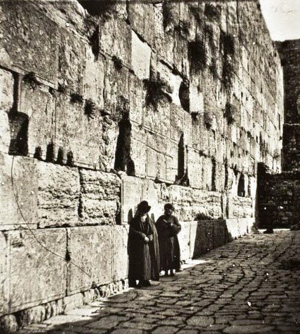

Suleiman the Magnificent, whose remodeling of the Old City in 1542 is still evident in the current city walls, gladly employed Jewish advisors, yet the sultan also reworked Jerusalem’s religious landscape in favor of Islam, Montefiore notes. It was under his rule that the Western Wall became cemented as a hub of Jewish worship, yet over time the Kotel, too, would become a battleground. In the early 20th century Grand Mufti Hajj Amin al-Husseini, a bigoted, unscrupulous rabble-rouser and Nazi sympathizer, tried repeatedly to chase Jews away from it, at times by instigating murderous riots.

The mufti rejected any offer of compromise from the Zionists over the fate of the city. During Israel’s War of Independence in 1948 the mufti’s Arab militiamen, aided by British officers, encircled Jerusalem’s 90,000 Jews. A terror attack on Ben Yehuda Street killed 58 Jews on February 22. In revenge Menachem Begin’s paramilitaries went on a rampage in the nearby Arab village of Deir Yassin, killing scores of women and children by tossing grenades into houses. On April 13, Arab attackers retaliated by massacring 77 doctors and nurses of Hadassah Hospital. “The gunmen mutilated the dead and photographed each other with the corpses splayed in macabre poses,” Montefiore writes. “The photographs were mass-produced and sold as postcards in Jerusalem.”

The eastern part of Jerusalem, along with the historic Old City, fell into Jordanian hands. Arabs looted and destroyed scores of ancient synagogues, including the one Nachmanides himself founded in the 13th century. Jordanian soldiers used Jewish gravestones for building latrines.

Come the Six Day War in 1967, Jerusalem passed fully into Jewish hands after two millennia. In coming decades a relentless string of terror attacks would take its toll on Jerusalemites, claiming yet more innocent lives as sacrificial victims for the murderous religious crazes the city has always inspired. Yet now at long last Jews do not need to “go away cowering” in Jerusalem.