If Religion IS the Quality of Our Actions…

…What does a decent and straightforward imam have to say about his fellow Muslims and about their shared faith? And what are nonbelievers to think?

Tibor Krausz

The Jerusalem Report, May 20, 2005

"What went wrong?" asks Bernard Lewis, the West's preeminent scholar of Islam, in the title of his watershed 2002 study. "Compared with its millennial rival, Christendom [now the West]," he elucidates, "the world of Islam ha[s] become poor, weak and ignorant." In other words, with its decrepit tyrannies much of the Arab world subsists on impoverished economies, revels in terrorism, and, well, doesn't seem to be much of a moral or intellectual leading light. So the question, on reflection, becomes more like "What didn't go wrong with Islam?"

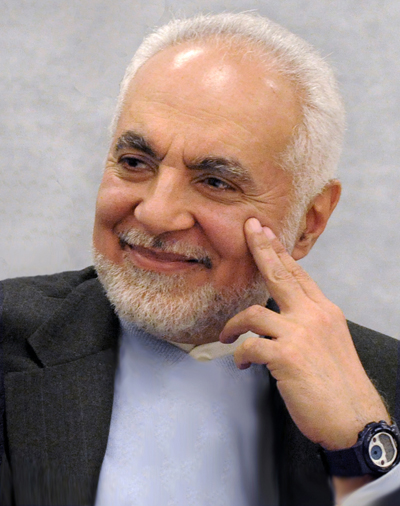

In "What's Right with Islam," Feisal Abdul Rauf attempts an answer. He's the Kuwaiti-born scion of an illustrious clerical dynasty; a regular fixture on the networks; and the imam of a mosque within walking distance of where the World Trade Center once stood. The erudite Rauf is popularly labeled a "moderate" Muslim -- in a tacit admission that moderate Islamic clerics are rare enough to deserve special mention. He cuts to the theological chase.

Islamic teachings, Rauf argues, are universal humanistic principles by virtue of their "Abrahamic ethic," which also runs through Judaism and Christianity and is innate to all humans by its two primary commandments: 1) Love God above all and 2) Love your neighbor as you love yourself. By emphasizing humans' God-given rights to "liberty, equality, fraternity and social justice," the Abrahamic ethic has provided the morality not only for the inherent goodwill of Islam but also for the American Declaration of Independence and Constitution. So much so, the United States, Rauf (a proudly patriotic naturalized American) stresses, is an "Islamic state" in that it embodies "the principles that Islamic law [sharia] requires of a government."

This is heady stuff, and you might wonder why countless Muslims follow Ayatollah Khomeini's lead in condemning the U.S. as "the Great Satan." Because, Imam Rauf explains, in propping up kleptocratic dictatorships for its selfish, short-term geopolitical interests, the U.S. has failed to abide by its own hallowed principles vis-a-vis the Arab world and has unwittingly helped fortify radical Islam by turning a blind eye to these regimes' successful elimination of all forms of political opposition.

The question Rauf leaves unanswered, though, remains not what — based on the merits of its humanistic teachings — Islam could and should be, but what, on evidence, it generally is these days. Judged by its daily manifestations worldwide, Islam can claim to be a propagator of "liberty, equality, and fraternity" the same way Christianity could style itself a doctrine of "love" during the Inquisition, witch-hunts and pogroms. "If a Muslim cannot find comfort in a world in which others are Christian, Jewish, Hindu, Buddhist, and agnostic," Rauf allows, "that person cannot claim to be following the teachings of the Quran and the Prophet Muhammad." Yet a mere two paragraphs lower we find this: "Islam's natural impulse is a globalized religion based on a set of universal principles that all of humanity can agree on" — what else but the universal principles of Islam.

It's how Muslims resolve this inherent paradox of their faith that defines Islam for non-Muslims everywhere. Yet even if nowadays the second option seems more heavily in favor from Iran to the Philippines, Rauf won't let Muslims off the hook of culpability. Properly understood, he explains, Islam is an attitude, not an ideology. And the faith's paradigm shift from being an act of piety to becoming radical Islamists' ideological weapon of choice has had dire consequences. "Defining Islam as a religious system rather than a universal act of submission [to God]," he writes, "has fed Islamic triumphalism and fueled modern Islamic militancy."

On closer reading, however, "What's Right with Islam" proves to be a learned yet unconvincing apologia in line with other recent defenses of Islam that leading "moderate" (read: pro-Western) Muslim scholars have scrambled to publish in the wake of 9/11. In downplaying or entirely disregarding Islam's more contentious teachings — the exaltation of martyrdom in advancement (not just defense) of the faith; the murder of infidels hailed as a VIP ticket to Paradise; the inherent misogynism of several Islamic teachings — Imam Rauf whitewashes, by default, even those fanatic excesses of contemporary Islam that have grown out of traditional teachings. He paints with a broad brush, leaving disturbing details safely blank.

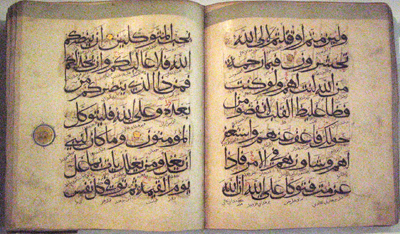

Yet the devil, as we know, is in the details. Like the Torah and the Gospels, the Koran isn't without its myriad contradictions. But Muslim theologians are further handicapped by Islam's founding principle of supersession, whereby the religion styles itself as God's unadulterated message to mankind (as received by Muhammad sutra by sutra, word for word in the primeval divine language of Arabic) and is accordingly seen by believers as the conclusive corrective to the incomplete and corrupted revelations of both Judaism and Christianity. Literal readings of the Koran, therefore, are not just desirable but obligatory. Needless to say, obdurate literalism can be dangerous business. Jews, for instance, are described in the Koran as implacable enemies of Muslims and labeled the offspring of "monkeys and pigs," whom the Prophet saw no choice but to slaughter. Perhaps not coincidentally, the Islamic world today is a hotbed of rabid anti-Semitism of the Third Reich kind.

A devout Muslim, Rauf declares Muhammad "the perfect human," a paragon of virtue whose example it is every Muslim's duty to follow. Considering that Muhammad was the sole recipient of God's presumed authoritative message to mankind via the Archangel Gabriel (who delivered Allah's words verbatim to the Prophet over two decades in snatches of oral revelations not written down and arranged until after Muhammad's death) the validity of God's Word hinges on the warrior-merchant's credibility — and his immediate followers' powers of retentive memory. Neither Muhammad nor the posthumous codifiers of his message, though, left leeway for doubt: they declared it a capital crime to question the infallibility of the Prophet's received revelations (just ask Salman Rushdie about the consequences of exegetical adventurism).

That's not to say, though, that Islam is a sham or, as evangelist firebrand Jerry Falwell would have it, a "diabolical" faith. Yet despite all the talk about Islam's having been hijacked by a tiny hardcore of extremists, Osama bin-Laden and Abu Musab al-Zarqawi may simply be the logical, if fanatical conclusions of fundamentalist trends in "mainstream" Islam. No religion exists in a theological vacuum but rather in the cultural milieu created by its adherents. And today that milieu worldwide is Wahhabism. Once a peripheral creed of desert Arabs on the extremist fringe in what is now Saudi Arabia, petrodollars from the country's vast oil reserves have solidified Wahhabism's supremacy at home and exported it wholesale around the Muslim world. Whereas medieval madrasas were centers of civilized learning and precursors to modern universities, today's Saudi-sponsored schoolhouses as far away as Indonesia double as recruitment centers for al-Qaeda's homegrown offshoots.

"In parts of the world where access to clean water makes all the difference between health and the misery of chronic dysentery," writes investigative journalist Kenneth R. Timmerman in his "Preachers of Hate" (2003), "Saudi charities have built 2.7 mosques for every well — and at considerably greater expense. " To wit: The devastating tsunami last December that killed more than 225,000 people around the Indian Ocean (most of them Acehnese Muslims) moved the Saudi government only enough to join the global outpouring of aid with a measly $10 million (later tripled under international ridicule). And this by a country that in 2002 organized a telethon to raise well over 10 times as much for the families of Palestinian suicide bombers. Imagine, Lewis writes in "The Crisis of Islam" (2003), that "The Ku Klux Klan obtains total control of the state of Texas [and uses its oil revenues] to establish a network of well-endowed schools and colleges all over Christendom, peddling their peculiar brand of Christianity."

And there you have him: the lionized holy warrior bellowing "God is Great!" while beheading his screaming victims with a kitchen knife. Religious doctrines, Rauf posits in a counterargument, never warrant violence in themselves; rather, the real underlying cause for terrorism is always political, economic, and sociological. "Religion is not the label that we attach to our actions," Rauf suggests, "but the quality of our actions." Eloquently said; the implication, though, that Muslim terrorists are merely sociopaths with perverted spiritual fetishisms dangerously underplays the actual content of conventional Islamic teachings. A pivotal Koranic doctrine divides the world into Dar al-Islam (House of Islam) and Dar al-Harb (House of War: i.e. anywhere else). Since Muhammad was the founder, as Lewis has pointed out, not only of a faith but also of a fast-expanding empire, Islam has from day one measured its success not least by the extents of its territorial conquests. (The time-honored apologia that "jihad" is a spiritual, not an imperialistically militaristic concept is a blood-drenched red herring.) Pious Muslims view their faith as the divinely sanctioned global community of Man, and so the secular West's unprecedented technological and ideological supremacy threatens not only Islamic societies' traditional ways of life but the very legitimacy of Islam as well.

In Islam, Rauf explains, "the building of a proper community life on earth is a supreme and religious imperative." The danger, of course, lies in how one interprets "proper community." Homicidal Jihadists from Iraq to Thailand find their answer in the annihilation of any alternative to sharia — off must civil liberties, democracy and pluralism all go. Imam Rauf comes across as an honest, well-meaning gentleman. Yet in refusing to tackle his religion's anachronistic doctrinal perversions, he unwittingly plays into the hands of radicals. By their conspicuous silence (or muted pooh-poohing at best) in the face of appalling barbarities perpetrated by their extremist brethren, even moderate Muslims seem to condone Islamic terrorism as sanctioned by the Koran: inferably, acts of Islamic terror are legitimate reactions to insufferable grievances inflicted on the faithful.

In a chapter titled "A New Vision for Muslims and the West," Rauf propagates an action plan to pre-empt further escalation in what scholar Samuel P. Huntington has called "a clash of civilizations." Rauf urges the U.S. to spearhead a global Winning-the-Peace initiative aimed at refashioning Islamic societies along Western lines by helping them create free economies, independent judiciaries, and governments answerable to their electorates. America's 7 million Muslims, meanwhile, must act as moderating influences in reconciling Islamic and Western values in the Muslim world, he proposes. Rauf quotes Rabbi Arthur Schneier, a champion of interfaith dialogue in the Balkans, who argues that any crime committed in His name is the greatest sin against God. Therefore, Rauf tells us, "Muslims need to cogently explain why, if Islam is a religion of peace, acts of terrorism are committed in its name."

Most importantly, though, the Abrahamic religions must work toward rapprochement so "the Cross, the Crescent, and the Star of David become symbols of peace, tolerance and mutual respect." Inshallah to that.