Blood Money

The grim story of a chemical combine’s fatal compromise with the Nazis, and its murderous consequences

Tibor Krausz

The Jerusalem Report, January 5, 2009

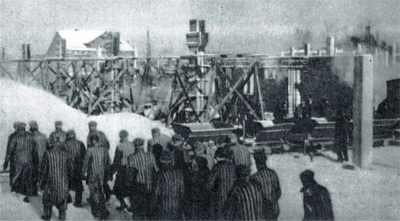

Scouting for a site for a new plant in late 1940, engineers of the German chemical giant IG Farben decided on a small town in Upper Silesia. It had much to recommend it: proximity to vital coal supplies, plenty of water sources and good transportation lines. The town of Auschwitz also had a small SS-run prison camp, which could be tapped for slave labor.

A large chemical plant was duly built — some two miles west of a new concentration camp. Inmates there would be chain-ganged into the production of methanol, a vital ingredient in aircraft propellants and explosives alike. “IG Auschwitz-Monowitz” began producing high-octane fuel and synthetic rubber tires for Luftwaffe airplanes as they rained death and destruction on much of Europe. Renamed, the chemicals plant continues to operate to this day as a leading producer of synthetic rubber in Europe.

The complicity of German industry in Nazi crimes is well documented. Many ex-collaborators remain with us as instantly recognizable brands. If Luftwaffe planes and Panzer divisions had boasted sponsorship logos, these wouldn’t look shabby on any racing car today: Daimler-Benz and BMW (aero engines); Siemens (radar, engines, anti-shrapnel pilot helmets); Zeiss (precision optics) Blaupunkt (electronics); Bosch (fuel injection); BASF (bombs, explosives).

Nor did German industry shy away from using POWs and concentration camp inmates as slaves. The practice worked magic with overheads as slave laborers required no wages and could be instantly replaced with new workers if worked to death (which happened constantly). In “Germany’s managerial elite,” noted Cambridge historian Adam Tooze, apropos German industrialists’ craven collusion with the Nazis, “[Hitler’s] regime found willing partners.”

Just how willing is apparent from a new history of IG Farben. In “Hell’s Cartel,” a Faustian tale of corporate sellout, Diarmuid Jeffreys, a documentarian-journalist, charts the chemical giant’s “slow but inexorable descent into moral bankruptcy” from before the Nazis even appeared on the scene. The conglomerate, which boasted several Nobel laureates among its scientists who pioneered “wonder drugs” like aspirin (whose Jewish inventor would be robbed of his credit before being sent to Theresienstadt) and in its prime employed a highly trained workforce of several hundred thousand, resorted to the use of slave labor as early as 1916. By co-opting the Kaiser’s army in World War I into dragooning hapless Belgian civilians and Russian POWs into work at understaffed German plants, Germany’s industrial chemists blithely set a precedent for the Nazis.

That’s not to say that IG Farben — a cartel of six German chemical heavyweights, including the drug maker Bayer, the photochemist Agfa, and the plastics manufacturer BASF (all of which remain industry giants), whose fortunes had been made on synthetic dyes and dominated the global chemicals market — was a singularly immoral corporation from the get-go. Rather, in Jeffreys’s telling (of a story well known), it was a process of moral compromise as IG Farben’s directors hitched their fortunes to the Nazis, creating a lethal symbiosis between industry and regime. Without help from the company’s ingenious scientists and hard-nosed managers, he argues, Hitler could never have launched and sustained his apocalyptic scheme of war and genocide.

* * *

By the time of Hitler’s accession in 1932, IG Farben was a formidable corporate giant rivaling the international business clout of America’s Standard Oil. The IG was, Jeffreys writes, “a mighty corporate colossus, a vast, sprawling octopus ... with tentacles reaching to every major country.” The German chemical industry was a world leader in the scientific alchemy of organic chemistry (the artificial reproduction of rare natural substances), and IG Farben would prove invaluable for Hitler both in the run-up to the war and through it.

In line with the Fuehrer's ukase for a self-sufficiency economy to allay Germany’s acute raw material shortages during massive rearmament, which brought a full-scale retooling of German industry, IG Farben spearheaded the production of high-quality synthetic rubber. By chemically synthesizing coal (which was abundant in Germany) into aviation fuel (which was not), the company also came up with a way to keep the Luftwaffe in the air. The company profited handsomely in return. During the war years IG Farben’s annual investment stood at half a billion Reichsmarks — a fiftyfold increase over a decade earlier when the Nazis came to power amid economic recession.

Whereas some businessmen and engineers (in the steel industry, for instance) sang to the Nazis’ tune only willy-nilly, those at IG Farben joined in the chorus enthusiastically. An IG Farben director, Carl Krauch, became an indispensable industry factotum in the service of the regime, busying himself as Hermann Goering’s plenipotentiary for chemical production. With 23 other company executives, Krauch would be tried at Nuremberg, where vice-chairman Georg von Schnitzler explained IG engineers’ eager collaboration as their professional duty to solve technological challenges posed by Hitler’s drive for autarky (which echoed Albert Speer’s own sham defense of apolitical technocracy).

German industrialists, though extremely patriotic, may not have been fully motivated in their complicity by National Socialist ideology, but they sure were by corporate greed. War was great for business. Light metals in Stuka bombers, high explosives, belt buckles, mess kits, plastic keys on Enigma encryption machines, even synthetic rubber-tipped windshield wipers — they all came courtesy of the IG for Hitler’s invasion forces. As the Nazis plundered occupied territories, the concern also shared in the spoils, acquiring prized industrial assets like Czechoslovakia’s Skoda Works, a leading arms manufacturer till then owned by the Rothschilds. “By the end of the war,” Jeffreys writes, “the mighty IG had become Hitler’s cartel.”

Even before Hitler came to power, the cartel’s directors rallied behind the Nazis. On Feb. 20, 1933, Hitler, newly installed as Chancellor, summoned two dozen leading German industrialists — IG Farben heavily represented among them — to a meeting at Hermann Goering’s private residence to ask for their support before parliamentary elections scheduled for March 5. They pledged 3 million Reichsmarks on sight with IG Farben alone contributing almost half a million marks into the Nazis’ coffers. (In the event, the Nazis were saved from the whim of German voters with the torching of the Reichstag, whereupon Hitler conveniently had himself appointed dictator.) IG Farben would remain the regime’s primary financier right until the end, also picking up the tab for the Fuehrer’s personal expenses.

"The whole venture just took off," he says, his hand swinging away like a plane at liftoff. "One month after I'd opened the first gym, I was making serious money."

Some historians have seen the episode as proof of German industrialists’ unprincipled servility and overt Nazi sympathies from the start. Jeffreys offers a more nuanced explanation, portraying it as a sign of self-serving opportunism, not ideological agreement. They were diehard nationalists, yes, but no virulent xenophobes — and were fairly liberal about economic matters. Carl Bosch, the cartel’s elderly visionary chairman, the writer points out, even pleaded with Hitler on behalf of IG’s myriad Jewish scientists, earning himself the Fuehrer’s lasting enmity. Bosch went on to help Jewish employees harassed out of their jobs.

Yet his principled stance didn’t become company policy. As Jewish employees were being purged, the “new guard” of younger managers eagerly did business with the Nazis already in 1933. By signing a lucrative government contract to produce 350,000 tons of synthetic gasoline annually, the chemists agreed to relieve Germany’s acute reliance on fossil fuel exports, thereby “providing Hitler with [some of] the means to launch the most devastating conflict in history,” Jeffreys writes.

And so the Faustian deal was struck with ever tighter cooperation — until, during the war, collaboration turned into criminal connivance.

* * *

Though Nazi ideologues remained single-minded in their genocidal aspirations, they saw fit to adapt mass murder to the exigencies of industrial production. Early in the war, Hitler and Himmler envisioned the Final Solution not as gassing Jews outright but rather working them to death as slave laborers in German industry and on giant construction projects in occupied Poland and Russia in a frenzied drive of Aryan colonization. Before scheduled extermination at death camps, Jews were duly rounded up for “selection” into hard-labor units with healthy young men and women spared immediate execution to meet their intended ends instead through Vernichtung durch Arbeit, or “destruction through labor.”

That policy suited IG Farben just fine. The company’s buna (synthetic rubber) factory at Monowitz fed off the concentration camp at Auschwitz. In fact, Auschwitz-Birkenau was first conceived by SS leader Heinrich Himmler (a failed poultry farmer turned self-styled economics mastermind) as a labor ancillary for IG Farben’s plant. The company's site would soon grow into its own as a separate concentration camp -- run by brutal company kapos with help from the SS — where “death came in a form profitable to the Third Reich,” as Jeffreys puts it. Few inmates lasted more than a few weeks. “By now,” the author notes, “the whole project had assumed a ghastly self-sustaining logic, seeming to be as much about the consumption of prisoners [35,000 in 1943 alone] as about producing synthetic rubber.”

At nearby Auschwitz, an IG Farben subsidiary made brisk business with a trademark product much in demand — Zyklon B for gassing Jews. IG Bayer, meanwhile, found the death camp a useful laboratory for its serological “research” in Dr. Josef Mengele’s experiments on select inmates, many of them children. Another doctor employed by the company wrote home enthusiastically to his colleagues in Leverkusen: “I have thrown myself into my work wholeheartedly to test our new preparations ... I feel like I am in paradise.” With such revealing details, Jeffreys leaves no doubt about company chemists’ culpability in Hitler’s crimes. His chronicle of IG Farben’s corporate history, from its formative years in the 1860s to its ignominious downfall a century later, is a meticulous, damning account of IG Farben told well with zing, although his strictly chronological retelling precludes a better-defined analysis of the pivotal war years (we’re nearly halfway through the 410 pages before Hitler even shows up). The reasons Jeffreys discovers behind the concern’s sellout — greed, unscrupulousness, hypocritical see-no-evil stance — may appear more selfish than manifestly evil, but therein lies IG Farben’s true iniquity: in its sycophantic pursuit of profits in the service of an unspeakable regime.

Few stories exemplify the dangers and self-defeating follies inherent in a scientist’s surrender to the vagaries realpolitik than that of Fritz Haber (which Jeffreys unfortunately recounts only in scattered footnotes). The flamboyant Jewish scientist, working at BASF, achieved chemistry’s equivalent of turning lead into gold by extracting nitrogen (essential for fertilizers and explosives and hitherto obtained from fast-depleting guano sources) from air as synthetic ammonia. He duly won a Nobel in 1918 for his achievements — but not before the proud German patriot went down in history as the man who pioneered the use of poison gas in modern warfare in 1915 at the Second Battle of Ypres.

Indirectly responsible for the agonizing death of numerous Allied soldiers, Haber drove his wife to suicide and escaped being tried as a war criminal only by fleeing incognito to Switzerland. Despite his contributions to the Fatherland, the Nazis later promptly disowned him. Haber died a broken man in 1934, but several members of his family were later gassed in concentration camps.

As Haber can testify with Faust, a pact with the devil, however lucrative at first, always ends in blood and tears.