Apes and the Origins of Religion

An anthropologist ponders how “an apelike creature capable of empathy and meaning-making developed into a species that sings the praises of God”

Tibor Krausz

The Jerusalem Report, May 28, 2007

Witness primates aping God — in synagogues, churches and mosques. Apologies if that sounds snide, but the point remains: According to evolutionary theory, religious faith is not a gift of God to privileged souls, but rather a biological function that, like any other of our natural attributes from opposable thumbs to speech, is presumed to be an evolved characteristic.

“Evolving God” is such a scientific attempt to “demystify” religion by accounting for its evolutionary origins. Inevitably, therefore, your views of anthropologist Barbara J. King’s arguments will be preconditioned by the mindset with which your approach her thesis to begin with. Believers may take umbrage at being informed that they’re essentially “ape[s] that evolved God.” Atheists, meanwhile, may appreciate the irony that not only have we descended from a primeval primate, but so too has God (or at any rate belief in Him).

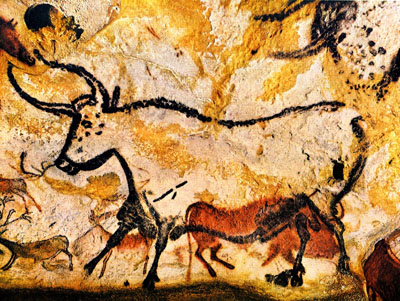

Explaining how faith became part of our psychological makeup remains a daunting task. For although anatomically modern humans have been around for some 200,000 years, the archaeological record has yielded no hard evidence of spirituality in our ancestors until the Later Stone Age, between 45,000 and 15,000 years ago. That was when an explosion in human thought and culture suddenly manifested itself in art, symbolic thinking and ritualized practices such as burials.

Beliefs don’t fossilize, so we can only infer prehistoric psychological and cultural patterns from the often scant and ambiguous archeological evidence (as well as by observing contemporary apes, surviving hunter-gatherers and development in children). Following such methods of “cognitive archaeology,” some theorists attribute the emergence of a religious mindset to more sophisticated tool-use by early humans and their attendant intellectual appreciation of cause-and-effect relationships.

Because our ancestors lacked the scientific methodology to understand the true causes of natural phenomena, the argument goes, they began attributing mystifying events (from lightning to disease) to magical and supernatural forces. They also started crediting physical forces with will and purpose: the wind had a soul, the forest was alive, animals were good or evil — and so animism was born. They then began constructing elaborate cosmogonies with divine mythologies, and tried to influence nature in their favor through increasingly rigorous rituals and taboos. Thus, more sophisticated systems of religion like Judaism came to be.

Other scientists speculate that religious belief may be a byproduct of enhanced introspection as humans began to reflect on themselves and the world around them. Or faith, yet others theorize, resulted from the emergence of articulate language about 50,000 years ago as a bulwark against verbal deception with early humans trying to establish incontrovertible “sacred truths” (of “The Lord our God, the Lord is One” variety). Or else.... Theories abound.

King, an anthropology professor at the College of William and Mary in Virginia, has another. Religion, she posits, arose from our emotional need to belong and connect while constantly interpreting and reinforcing our relationships. We do so through symbolic social rituals, which are “a key to the expression of the religious imagination.” Quoting Martin Buber that “man becomes an I through You,” King defines religion much less as a doctrinaire set of theological arguments about the nature of the world than as a symbolic, cultural tradition of emotional attachment and moral conduct expressed through ritual: “an active expression of belongingness aimed at a spiritual realm.”

To most of us familiar with religious tenets, that may seem a rather reductive definition of many a religion, not the least of whose attributes is an insistence on a comprehensive worldview founded on absolutist claims that encompass everything from Creation to the End of Days. No religious dogma about the nature of the world has held up under closer scientific scrutiny, and so whereas revealed religions continue to assert that we can never be religious enough (there could always be stricter observance or further penitence), science ponders the reverse: Why are most of us still religious at all? It’s because, King posits, since our biological lineage diverged from the apes’ between 7 and 5 million years ago, the human religious imagination has “developed in ever-widening circles of engagement from immediate social companions, to members of a larger group, then across groups, and eventually to a wholly new dimension, the realm of sacred beings.” By implication then, the process continues.

Yet while the strengths and complexity of humans’ beliefs may be unique among animals, she adds, the emotional needs that underlie them aren’t. Our closest evolutionary relatives have them, too. Primatologists have indeed long documented such “humane” emotions in chimpanzees, bonobos and gorillas as empathy, affection and altruism. The great apes also display rudimentary forms of tool use, self-awareness and theory of mind (the ability to figure out another’s mindset or intentions). When it comes to social life, Frans de Waal, a leading specialist in primate cognition, asserts in “Our Inner Ape” (2005), “there is not a single tendency that we do not share with these hairy characters.”

And that, presumably, includes religion as well. After a fashion, yes, says King (who studied baboons and gorillas in Africa). Primates’ unique capacity to bond, emote, rejoice, fear, lament and commiserate, she maintains, echoes our own boundless (and evolved) religious imagination, which gives vent to all these emotions. Mother-infant bonding, intuitive compassion and sorrow over the death of a relative are evidence in apes, if not for actual spirituality, then for its biological underpinnings, she suggests.

The problem with this argument is that it leaves atheists collectively out in the cold. After all, they, too, evidence all the deep emotions characteristic of believers: they just often attribute their causes to different sources. Then spare a thought to the import in Judaism of cerebral commitment, and King’s emphasis on emotion as the primary motivating factor behind religion may seem further misplaced.

* * *

Already in the mid-19th century, Charles Darwin argued that the biological reason for the evolution of religious faith lay in its survival value. That is, early humans who exhibited a mental capacity for faith — as well as other abilities like speech — had a better chance for survival, perhaps by being more socially cohesive. Over numerous generations, “believers” bequeathed this adaptive trait to their offspring until religiosity (or at least a predisposition to it) became a biologically hardwired feature of us.

In “Evolving God,” readers familiar with evolutionary theory about human origins will find much rehashed from popular primers on the subject without apparent benefit to the thrust of King’s central argument. Digressions also lend some passages a New Ageist feel, with en passant forays into Native American holistic atavisms bringing you up short as you wonder how that ties in with the ongoing discussion about ape psychology.

When King does get into her stride, she takes you on a provocative (if sometimes still meandering) intellectual journey. Drawing on Canadian archaeologist Brian D. Hayden’s controversial ideas, she favors the hypothesis that the first stirrings of a religious imagination date much farther back than generally assumed, to hundreds of thousands of years ago. From the evidence she cites for this hypothesis, it is evident that, quite apart from the Biblical narrative, the Holy Land should retain a pivotal role in our understanding of religion’s evolutionary origins thanks to valuable archaeological finds in Israel and nearby.

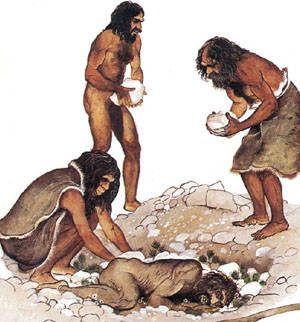

On the “Venus of Berekhat Ram,” a basalt figure unearthed on the Golan Heights in 1986 and dated to 230,000 years ago, traces of red ocher (a pigment obtained from iron oxide) were found, indicating the humanoid-shape object’s possible ritualistic use. Clues indicating the possible development of symbolic thought in humans much earlier than previously suspected was also discovered in Israel. At Kafzeh Cave, south of Nazareth, the bones of people buried some 100,000 years ago were found to bear the same red substance long associated with death and sacred ritual in prehistoric cultures. (Tantalizingly, Adam’s name is derived from the Hebrew for earth, adamah, which also has the same root as adom, red.)

Then there’s Moses. Not the archetypal prophet, but a Neanderthal man dubbed Moshe by Israeli archaeologists who found him in Kebara Cave, near Caesarea. The prehistoric man died some 60,000 years ago and was laid to rest in a posture indicating proper burial. Meanwhile, at Regourdou in France, other hulking Neanderthals (opportunistic cannibals though they were, who inhabited Europe and parts of the Middle East between 130,000 and 27,000 years ago) buried one of their own in an apparent ritual, possibly testifying to their incipient belief in an afterlife, King posits. (Note the qualifiers — skeptical archaeologists will vehemently disagree with such interpretations of the find). This, King argues, should tell us not only that Neanderthals could think symbolically but that members of this hominid species were also intensely emotional — both of which attributes are hallmarks of spirituality. If so, we’ve been dethroned as the sole ever hominid guardians of spirituality.

Here’s a caveat, though: King bases her hypothesis not on verifiable patterns in the sparse but available archaeological evidence but rather on anomalies in it. Such conjecture, however informed, adds an extra layer of speculative uncertainty to already prevalent ambiguity.

What’s not in doubt is this: By the end of the last Ice Age (some 10,000 years ago) Neanderthals were long extinct, yet Homo sapiens — us — was a fully fledged spiritual animal. The first known temple in history dates to around 9,000 B.C. at what is now Gobekli in Anatolia, Turkey. The massive stone monolith decorated with animal figures and explicit scenes of human carnality was probably a major pilgrimage site for prehistoric hunter-gatherers in the area. Simultaneously, with sedentary life and the rise of agriculture in the Neolithic (10,000 years ago) came a quantum leap in organized religion. The first known settled agriculturalists were the Natufians, who lived in and around Israeli from 15,000 years ago: they believed in an afterlife and kept their dead ancestors close to home.

Soon, people around the Near East would erect magnificent ziggurats in Mesopotamia and pyramids in Egypt, both of which ancient religious centers would find prominent place in the Bible and heavily influence its traditions.

* * *

From primordial apes to emotive hominids to pyramid builders to religious zealots — was that the course of our spiritual awakening? From a scientific perspective: most probably.

So where, we may wonder, should that knowledge leave people with an unceasing longing for God?

Rejecting the extreme naturalistic view that Biblically inspired religions are nothing but culturally sanctioned superstitions harkening back to a benighted era, King advocates a compromise between modern scientific atheism and time-honored spirituality. Quoting Buber again that the sacred is “wrapped in a cloud [yet still] reveals itself,” she invites us to ponder a sublime mystery: How “an apelike creature capable of empathy and meaning-making developed into a species that sings the praises of God.”

Her book won’t be the last word on that monumental question, yet it makes for a thought-provoking read.