Knee-jerk anti-Zionism

Animosity to Jews and Israel is nothing new. It’s one of the oldest themes in the history of left-wing ideas

Tibor Krausz

The Jerusalem Report, December 17, 2012

Karl Marx thought he had the Jews figured out. “What is the worldly religion of the Jew? — Huckstering. What is his worldly God? — Money,” the patron saint of communism opined in his 1844 polemic “On the Jewish Question.” He went on to lament the way Christians had fallen prey in their habits to the pecuniary obsessions of those greedy Semites.

“This race poisons everything by meddling everywhere,” agreed the prominent French socialist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon in 1847. He advised: “Do not admit them to any kind of employment... The Jew is the enemy of the human race. One must send this race back to Asia or exterminate it.”

Anti-Semitism has long been seen as the exclusive preserve of the right, but the left has hardly been immune to its own virulent streams of Jew-hatred. Two new books lift the lid on that dirty little secret.

The first is “Israel and the European Left”by Colin Shindler, a historian at the School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London. In a series of somewhat disjointed chapters, Shindler tackles European socialists’ evolving, and often regressive, views of Jews and Zionism from the rise of Marxism to the Oslo peace process.

It’s an instructive read. Although it lacks a coherent narrative or much analysis, it’s packed with illustrative vignettes and a treasure trove of anti-Jewish quotes by leading leftists. The author has a rich lode of history to mine, and mine it well he does.

In “From Ambivalence to Betrayal,” Robert S. Wistrich paints on a much larger canvas. Professor of European and Jewish history at the Hebrew University and the head of the University’s Vidal Sassoon International Center for the Study of Antisemitism, as well as a contributor to these pages, Wistrich fills in the blanks, with bold analytical brush strokes, about leftist anti-Semitism’s long and rich history with myriad examples.

Apart from being a leading expert on anti-Semitism, Wistrich is eminently qualified to address the left’s anti-Jewish animosity: he was once a leftist radical himself. Born in Kazakhstan, then part of the Soviet Union, during the Stalinist era, Wistrich embraced the secular utopianism of radical Marxism before finding himself increasingly disillusioned after the Red Army’s invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968.

“I can still remember young French students chanting ‘We are all German Jews’ in the streets of Paris in May 1968,” he recalls. Today, now that many leftists have hitched their wagons to the cause of radical jihadists in their implacable opposition to the Jewish state, he adds, “such a march in the streets of Europe would be more likely to echo to calls of ‘Death to Israel,’ ‘End the Holocaust in Gaza,’ or ‘Hamas, Hamas, Jews to the Gas!’”

In his minutely researched magisterial account, Wistrich ranges far and wide over the Judeophobia of assorted leftist luminaries: it makes for illuminating, if depressing reading. Then as now, many Jewish progressives were also prone to intemperate bouts of Jew and Israel bashing.

***

Both Jewish socialism and Zionism arose from the same 19th century post-Haskala milieu: an increasingly self-conscious community of urbanized Jewish intellectuals who sought to drag Eastern European Jewry out of the demoralizing and stultifying confines of ghettos and shtetls. Their competing prescriptions — complete assimilation versus modern nationalism — would define Jewish politics for generations.

Jews gravitated towards the nascent socialist movement right from the start, seeing in the liberation struggle of the proletariat a long-awaited cure-all for the ills of the world. For many of them, revolutionary socialism provided a temporal blueprint for “repairing the world” in the rabbinic tradition of tikkum olam.

Yet few Jewish communists across Central-Eastern Europe identified with their Jewish roots. Instead, they pinned their hopes on an idealized image of the international proletariat’s innate virtues. They sought to break Jews out of their marginalization by submerging them in the classless, homogeneous mass of comrades. A good socialist was someone who refused to place tribal loyalties above universal solidarity for the downtrodden.

Offering a rival ideology for emancipation were the Zionists, many of whom were ardent socialists themselves. Dismissing full-blown assimilation as a pipe dream, they envisioned instead an independent Jewish state, which would best guarantee the rights and safety of Jews. To most Marxists, however, that idea smacked of “bourgeois nationalism.” Revolutionary Russian Jews, a young Chaim Weizmann reported bitterly to Theodor Herzl in 1903, showed “antipathy, swelling at times to fanatical hatred” to Jewish nationalism.

Yet despite their competing prescriptions for Jewish emancipation, both Jewish socialists and Zionists often drew heavily, wittingly or unwittingly, on their shared cultural traditions. Hebraic religious messianism, Wistrich writes, found a new lease on life in “the secular Marxist dream of collective redemption.” In the Communist utopia “the chosen people” would become members of “the chosen class.”

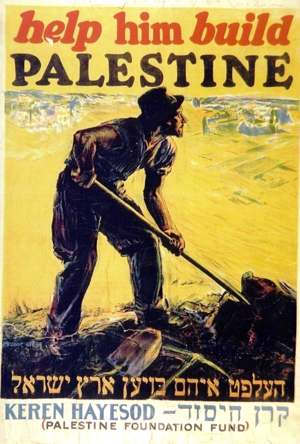

Zionist socialists, also fierce secularists, were in turn, he says, “driven by a quasi-religious pioneering fervor to transform the ‘Promised Land’ into a Jewish ‘national home’ ... where Jews could again become sovereign masters of their own fate.” They saw Palestine as an ideal ground for building communism from scratch thanks to the socialist collectives of the kibbutzim.

***

Historically, the Jews didn’t really fit the Marxist template of an ideal community of the oppressed. Yes, they had been much persecuted and, yes, most of them lived in dreadful squalor. But many of them also strengthened the ranks of the bourgeoisie: bankers, capitalists, moneylenders. That contradiction would haunt Marxist views of Jews.

The Russian revolutionary Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, partially Jewish on his mother’s side, saw anti-Semitism as the legacy of a reactionary bourgeois mindset and attributed Jewish socialists’ concerns about it among Russian peasants and workers to a “Zionist fable.” “Lenin wanted to assist all Jews in escaping their Jewishness,” Shindler notes.

Yet Lenin could wax lyrical at times about Jews, comparing their discipline and industriousness favorably to those of “boorish” and boozy Russian peasants, Wistrich points out. The socialist writer Maxim Gorky equally admired Jews, “the old, thick yeast of humanity,” for their “heroic idealism,” “tireless pursuit of truth,” and revolutionary spirit. He attributed anti-Semitism to simple envy of Jewish abilities and achievements.

Still, ideology trumped sentiment. Following the revolution of 1917, the Bolsheviks, whose ranks and upper echelons included numerous Jews, set about dismantling homegrown Zionist organizations. Often Jewish Bolsheviks eagerly lent the new regime a hand. Not even anti-Zionist Bundists escaped being labeled “chauvinists” and “separatists” merely for seeking an autonomous Jewish identity in the new Soviet Union.

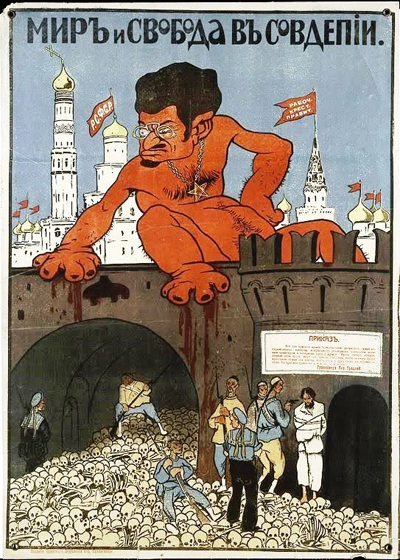

It is clear from both books that many shopworn canards used widely by leftists today to discredit Zionism originate in Soviet propaganda. As early as the 1920s, foreign communists viewed attacks on Jews in Palestine as the justified manifestations of “a national liberation movement” against “the Zionist fascist bourgeoisie.”

Not even the kibbutzim, which found parallels in Soviet collective farms, impressed Lenin. He insisted that what Zionist socialists did in Palestine was to suppress “the Arab working people of [the land]” — even as many local Arabs themselves saw socialist Zionists as agents of Soviet-style Bolshevism.

For decades thereafter, Soviet intellectuals and the country’s media would rehash calumnies about a worldwide Jewish/Zionist conspiracy. We can partly thank Stalin for that.

During Israel’s War of Independence, Stalin threw the Soviet Union’s weight momentarily behind the Jewish state. He saw Israel as a potential bridgehead for Soviet influence in the Middle East, but those “circumcised Yids”, as the Soviet dictator at times called Jews, had never really been close to his heart. Fearing “dual loyalties” among Russian Jews, Stalin began to view them as potential fifth columnists for Zionism. By then he had liquidated Soviet leaders of Jewish extraction, including Leon Trotsky (né Bronshtein), Grigory Zinoviev (né Apfelbaum) and Lev Kamenev (né Rosenfeld), all Soviet patriots with no love for the Zionist cause.

Stalin was a consummate political opportunist who relied heavily on Jewish comrades when it suited him and turned against them when it didn’t. He called anti-Semitism “an extreme form of racial chauvinism,” and one of his closest underlings was the Jewish Bolshevik Lazar Kaganovich. That, though, didn’t stop the Soviet leader from engaging in crude stereotyping of Jews for comic effect during his interminable nocturnal drinking bouts at his dacha.

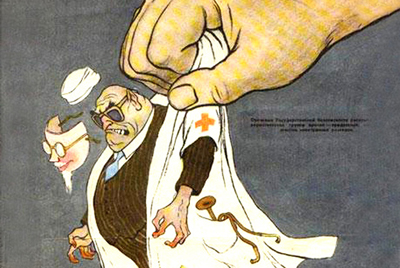

Wistrich, however, sees Stalin as a diehard anti-Semite with latent Judeocidal tendencies. He points to Stalin’s pending purge of Russian Jews during the Doctors’ Plot in 1953, when several Jewish doctors came to be accused of scheming to murder Soviet leaders at the behest of the CIA and the Zionists. Only Stalin’s death in March that year saved them from purges and possible deportations. “From being an anti-anti-Semitic state in the early 1930s,” Wistrich writes, “the USSR would henceforth steadily turn into a powerhouse for the new style of anti-Jewishness [i.e. anti-Zionism] and the delegitimation of the Jewish homeland.”

Soviet propagandists began resorting to crude Nazi stereotypes of Jews; for good measure they also cooked up new libels like the absurd claims that it was Zionist conspirators who had been behind the Holocaust, and that Hitler had been inspired by Herzl in his hatred of “impure races.”

“[T]he Holocaust inversion of the Left, which execrates Zionism as a form of Nazism,” Wistrich says, is a legacy of Soviet propaganda, which also pioneered the coupling of the Nazi swastika with the Star of David. Pravda cartoons, meanwhile, regularly depicted Israel’s leaders as modern-day Nazis who had outdone Hitler in their crimes.

That sort of vile propaganda is still alive and well, not least in British academic discourse and newspapers like The Guardian. “This conscious attempt to ‘Nazify’ Judaism, Zionism and Israel” writes Wistrich, “deserves to be regarded as one of the most scandalous inversions in the history of the longest hate.”

***

What little goodwill that remained on the European left towards Israel pretty much evaporated after 1967, when the image of “the jackbooted Jewish conqueror emerged, aided and abetted by a coordinated Jewish lobby which was centrally pulling the political strings in a multitude of countries,” Shindler writes. The view — propagated in large part by Jewish Marxists like Isaac Deutscher and Noam Chomsky — that Israel was a racist colonial transplant in the Arab heartland became unshakable.

Within days of Israel’s victory against Moscow-allied Arab nations in June 1967, Wistrich notes, Soviet “experts” would revive all the usual tropes in the anti-Semite’s playbook from a Jewish world-conspiracy to racist Zionists’ genocidal aspirations. They even rewrote the history of the pogroms as long-suffering Russian peasants’ fitting responses to their brutal and parasitic Jewish exploiters.

Hypocritical? You bet. Even as leftists have harrumphed about the right of all minorities to self-determination, they have denied that same right to Jews. Aware of the contradiction, they solved it by delegitimizing the Jewish state: it was so inherently an unjust, racist, unviable and artificial entity that it simply didn’t deserve to exist. Palestinian and Arab leaders soon turned leftist anti-Zionism to their advantage. They recast their implacable hostility to the Jewish state, formerly anchored in religious and pan-Arabic ideas, into progressive talking points of native rights and anti-colonialism to appeal to a Western audience.

The problems with the left’s anti-Zionism-at-all-costs dogmatism, both Wistrich and Shindler point out, weren’t lost on such leading socialist thinkers as Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, and Michael Foucault: they all defended Israel’s right to exist. The British Jewish Marxist thinker Ralph Miliband bemoaned the left’s “truly Pavlovian predictability to the [anti-Israel] slogans used to make it drool on cue.”

Nevertheless, routine vilifications of Israel have since migrated from the Marxist left to the political center, becoming received wisdom among European progressives. The Palestinian struggle is painted as a latter-day liberation movement of dispossessed Third-World natives armed with rocks resisting unscrupulous European-born colonizers. And if that view necessitates overlooking both a century’s worth of Arab intransigence and the openly genocidal aims of Hamas and Islamic Jihad, so be it.

“The [left’s] ideological contortions to make theory fit reality were profound,” Shindler notes. “The narrative of Israel as a colonial settler state,” he adds, “was easier to absorb than the unique complexity of the [Israeli-Palestinian] conflict.” On that score, too, Wistrich agrees. In the left’s view of history, he writes, “empirical facts are continually bent to the ephemeral whims of politics and narrative fashions.”

The very word “Zionist” has been turned into a catch-all term of abuse and recrimination. While leftists turn a blind eye to the crimes of self-styled “anti-colonialist” dictators like Robert Mugabe, Fidel Castro and Hugo Chavez, to say nothing of the Chinese Politburo, Wistrich says, they fall over themselves in excoriating Israel at the flimsiest of excuses. “One might wonder if this is not an ‘anti-colonialism’ of frauds and fools,” notes the scholar, who calls rabid anti-Zionism “a serious mental derangement.”

So it’s no surprise that leftist discourse today consists of pervasive, if pathetically illogical, conspiracy theories. But that’s nothing new, either. Oft-voiced phantasmagorias of a shadowy “Zionist lobby,” which allegedly holds the West’s financial and political institutions in its viselike grip, are just a new take on an old calumny: “the Rothschild myth in the 19th century,” in Wistrich’s words. Israel’s inherent iniquity, he argues, is “as self-evident to [anti-Zionist leftists] as was the ‘cursed’ condition of the Jewish people in medieval Christian demonology.” By now, Shindler concurs, Israel-bashing has become a default position across much of the left — a litmus test of ideological conformity to “progressive” values.

The shared message of both scholars’ works is this: There’s nothing radically new or particularly iconoclastic about leftists’ anti-Zionism, despite the self-congratulatory posturing of many modern progressives. In fact, it’s one of the oldest themes in the history of left-wing ideas — and one that no amount of reasoned argument or political reality will clearly ever discourage.