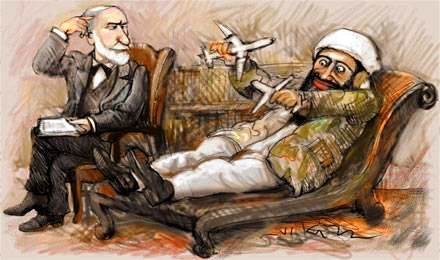

A Loon with a View

An in-depth examination of what motivates terrorists suggests that they can be defeated — eventually

Tibor Krausz

The Jerusalem Report, July 7, 2008

A father straps bombs to his one-year-old infant to serve as lethal bait to a female politician appearing at a political rally. Anyone who could do such a thing, our instinctive reasoning goes, must be deranged or unbearably desperate. We don’t know the mental state of the Pakistani militant who did just that last year in an assassination attempt on Benazir Bhutto, but your average terrorist is neither deranged nor all that desperate.

Study after study has shown that most terrorists, be they Red Brigade guerillas or al-Qaeda militants, aren’t psychopathic foam-at-the-mouth characters. Rather, they’re relatively well-adjusted individuals from comparatively well-to-do families. In person, they may sound reasonable, or even pleasant. As with cold-blooded genocide, so with brutal acts of terror, our very frame of reference, constructed on civilized norms, seems woefully inadequate to understand perpetrators’ motivations.

In a revealing chapter of his insightful new book “The Mind of the Terrorist,” Prof. Jerrold M. Post, a terrorism expert at George Washington University, recounts his lengthy interview with Omar Rezaq, a member of the Abu Nidal Organization, an extremist Palestinian group. Rezaq was responsible for murdering in cold blood two Israeli and three American passengers onboard a hijacked EgyptAir flight in Malta in 1985. Post, a trained psychiatrist and political psychologist, was an expert witness for the prosecution during the Jordanian-born Palestinian’s trial by an American court in 1996, after Rezaq had pleaded innocent by reason of insanity. Rezaq was mentally unstable, his lawyers maintained, as a result of Palestinians’ “collective trauma” under Israeli occupation.

So was he insane? Not in any psychologically definable manner, Post says. He recalls meeting a “cool, logical, calm” man, who recounted matter-of-factly how, exasperated by the sluggish pace of negotiations at an airport in Malta, he grabbed an Israeli female passenger by the hair and “blew her brains out.” Then he had “a very nice lunch,” Rezaq told Post, and proceeded to execute another Israeli woman and three Americans before the plane was stormed, resulting in the death of over 50 more passengers.

Did Rezaq’s placid Dr. Jekyll exterior hide a beastly and uncontrollable Mr. Hyde within? The reality is more prosaic, Post explains. In people like him, any sympathy or empathy for the hated “enemy” has been suppressed or entirely deprogrammed. Rezaq, now serving a life sentence in a U.S. prison, knew full well what he was doing; he just didn’t think Israelis and Americans deserved mercy. Historians of the Holocaust have found similar mental states in perpetrators who were frequently so calm and collected that they murdered Jews methodically in orderly shifts. Post cites Martha Crenshaw, a terrorism expert at Stanford University, who seconds Hannah Arendt’s observation about the banality of evil by noting that “the outstanding common characteristic of terrorists is their normality.” So much so, Post says, that terror groups carefully weed out excitable individuals.

If excitability isn’t a useful trait in a prospective terrorist, though, susceptibility is. Alienated, testosterone-fuelled youths, Post says, are sitting ducks for clandestine organizations, which ostensibly offer them meaning and personal fulfillment in an in-group’s collective identity. Trained handlers tap new recruits’ frustrations and pent-up aspirations, manipulating them into unquestioned obedience to a radical cause. Just as many a teenager in New York tries to emulate cultural heroes, like New York Yankees players, Palestinian youths aspire to become heroes by their own community’s standards -- by joining the glorious pantheon of shahids, or martyrs.

Pivotal in terrorist indoctrination is the demonization and dehumanization of the enemy: It’s not human beings you face, and must kill, but merely parasites and demons in humanlike guises. “[H]atred is bred in the bone,” as Post puts it. And so Hamas, espousing a venomous cocktail of medieval blood libels, Nazi racist claptrap and traditional Islamic Judeophobia, spares no effort in inculcating young Palestinians, from the cradle up, in a visceral hatred of "nonhuman" Jews — the “sons of monkeys and pigs,” as a verse in the Koran has it (5:60). Post cites a sign on the walls of Hamas-run kindergartens (where tots are at times dressed up as suicide bombers for birthday parties): “The children of the kindergarten are the shahids of tomorrow.” Meanwhile, in matinee shows on Hamas’s television channel kids are urged to emulate Assud, the “Jew-eating rabbit.”

This culture of hatred and martyrdom has been so effective that whereas in the early 1990s suicide bombers handpicked by Hamas were impressionable, unemployed, uneducated youths between 17 and 22, today’s recruits comprise mostly enthusiastic volunteers, both men and women between 13 and 55. “The socialization is occurring largely within society (no longer within closed cells),” Post writes, so that new recruits “require very little indoctrination, only technical training.” They’re “already primed and ready to explode.”

* * *

Terror groups come in different shapes and sizes — from national separatists (ETA, IRA) to social revolutionaries (Red Army Faction, FARC), single-issue advocates (Animal Liberation Front, bombers of abortion clinics), and religious fundamentalists (Hamas, Hezbollah, al-Qaeda). Invariably, the most implacably murderous, as Post’s book and statistics alike make it clear, are religiously inspired, claiming as they do divine mandate for their actions. Not even in their bloodiest prime would IRA or ETA stalwarts have resorted to the type of wanton savagery visited daily by Islamic fanatics upon longsuffering citizens (many of them fellow Muslims) in today’s Iraq, Afghanistan or southern Thailand. A rigorous online tally (www.thereligionofpeace.com) shows that since Sept. 11, 2001, more than 11,000 — and counting — documented terror attacks have been carried out worldwide under the banner of Islam.

An exception would seem to be the Tamil Tigers, a Marxist nationalist and so nominally secular group. It, too, is engaged in relentless suicide bomb attacks. Yet the carefully massaged cult of Velupillai Prabhakaran, the movement's enigmatic mustachioed “Leader, [who] can do no wrong,” as his followers testify, has elevated the terror kingpin to the status of a venerated Hindu divinity whose very name “inspires awe” in the rank and file. Foot soldiers are eager to lay down their lives in his service, not unlike Japanese kamikaze pilots in WWII brainwashed into “honoring” themselves by dying for the divine Emperor.

What degree of single-minded, callous bloodlust does it take to strap explosives on two local women suffering from Down’s syndrome, send them off to crowded marketplaces and blow them up by remote control, as al-Qaeda insurgents did in Baghdad last February?

Religious fanaticism thrives on, and fosters, a mindset of uncompromising self-righteousness that is wholly alien to conventional norms of moral conduct. The radical knows and abides by no law but that of his own incontrovertible creed of absolute certainty. Murder comes to be seen not as a sin but as a cleansing act of virtue in the service of a (usually amorphous) utopian ideal. The infliction of death — and the acceptance of it for oneself in return — is deemed necessary, or even desirable, to usher in a world remade on new terms. Such high-minded nihilism, some scholars argue, derives from apocalyptic traditions inherent in all three monotheistic religions, which predict history to culminate in a redemptive state of bliss following a purgatory of purifying bloodshed.

The Polish-born English novelist Joseph Conrad captured the essence of this mindset a century ago. In his prescient masterpiece “The Secret Agent” (1907), an anarchist professor roams the streets of London with explosives strapped to his deformed body, taunting his pursuers with his proclaimed superiority of purpose: The decadent masses cling to their miserable lives, Professor X proclaims, “whereas I depend on death, which knows no restraints.” Compare that to a boast by an Afghan mujahid: “The Americans love Pepsi Cola, but we love death.” Claiming God’s eternal word as their mandate, Islamic radicals show derisive contempt for life-affirming “manmade” concepts like democracy, liberty and creature comforts.

In interviews conducted by Prof. Post and Ehud Sprinzak, the late Israeli terrorism expert, incarcerated Palestinian Islamists gave a chilling insight into a callous bloodlust that flirts with genocidal aspirations. “The aim was,” explained a Fatah member, “to kill as many Jews as possible and there was no moral distinction between potential victims, whether soldiers, civilians, women or children.” If only they’d had weapons of mass destruction, said another Palestinian militant, “I would not have had any problem with 200,000 casualties.”

Unlike commentators who prefer to ignore or dismiss such ominous threats, Post recommends taking extremists at their word. “If one really wants to understand ‘what makes terrorists tick,’” he writes, “the best way is to [listen to] them.” And he does. Post provides revealing illustrations of the terroristic mindset, from IRA henchmen to Palestinian martyr wannabes, straight from the horse’s mouth. Rather than psychoanalyze them at the risk of reading interpretations into their views and actions, he lets terrorists speak for themselves — in words collated from interviews by interrogators, scholars and journalists.

This approach acquaints us directly with terrorists, as they offer rationally formulated justifications for murder while bragging about successful missions. Their narcissism often masquerades as self-sacrifice. A would-be Palestinian suicide bomber, later captured, recalls feeling “slighted” at not being selected for a “martyrdom operation” planned for Jerusalem.

* * *

Political terrorism has a long and bloody history, stretching back two millennia to the 1st century Jewish Sicarii (“dagger-bearers”) — the prototype terrorists (as scholars generally label them) who strived to liberate Roman-occupied Palestine by assassinating Roman officials and perceived Jewish collaborators. As all it takes for a new terror act is a fanatical individual with some knowhow (a Timothy McVeigh, say), terrorism won’t be eliminated any time soon.

Yet, it can be contained, Post suggests. Terrorism is an extreme form of psychological warfare with violence as its medium of communication. Groups like al-Qaeda are also expert manipulators of new media like the Internet. More than anything, Post says, it’s the terrorists’ message that needs combating.

Terrorists like to paint themselves as the real victims (of Israeli or U.S. aggression, perceived insults by Danish cartoonists, the presence of “infidels” on sacred Muslim soil). A prevalent Western attitude to accept such claims at face value only plays into the hands of extremists by legitimizing their culture of homicidal grievance. The task instead, Post suggests, is to “de-romanticize the terrorists [who] are not martyrs but murderers” through wide-ranging economic, social and educational initiatives on their home turf.

A fraction of the massive armament expenditures in Iraq and elsewhere, he points out, would suffice to provide secular education to millions of impoverished children (a mere $80 per child annually in Pakistan, for instance) whose only access to schooling today is at the “suicide bomber production lines” of Saudi-funded extremist madrassas, in the words of Israeli expert Ariel Merari. Yet even if undertaken immediately, Post cautions, such approaches will take decades to bear lasting fruit.

We’d better brace ourselves for plenty more terror to come.