The Guided Jewish Tour

Ben G. Frank embarks on an enviable itinerary; sadly he fails to take us along for the ride

Tibor Krausz

The Jerusalem Report, July 2, 2012

There is a certain pathos to the life of Jews in far-flung places. A few hardy souls, usually elderly, often neglected or beleaguered, hold on to vestiges of religious ritual in tumbledown old synagogues in a last-gasp attempt to remain Jewish. Their struggles can make for poignant tales and are rich material for writers and journalists who come calling in search of those private little dramas that are inherent in conflicts of identity.

Then there’s the other type of “Jewish World” story: the tales of Jews abroad. A member of any other ethnicity on a prolonged stay abroad is simply an expat; a Jew is a citizen of the Diaspora – a sort of geographical purgatory, a halfway house between exile and redemption. Theology considers all Jews outside the Promised Land to remain in a state of exile, even if they have never set foot in Israel and feel perfectly at home in the land of their birth..

In The Scattered Tribe, Ben G. Frank has both kinds of Jews in his sights. Frank, who is billed by his publisher as one of the US’s “most distinguished travel writers and commentators on Jewish communities around the world,” is the author of several travel guides, including “Jewish Europe” and “the Jewish Caribbean and South America.”

This time around he sojourns from Russia to Cuba with Vietnam, India, Myanmar, Morocco and Tahiti along the way. That’s an enviable itinerary. Sadly, the author fails to take us along for the ride.

Frank chronicles his experiences in the style of travel guide writers, which doesn’t benefit a book intended to be more in the genre of reportage than guidebook. He often lapses into travel brochure prose, complete with tips on where to eat, what to do, where to shop and when.

“Step up from the waterfront area and you will behold inviting shops, especially jewelry, including of course pearls, pearls and more pearls, pearls by the thousands and at all prices,” he writes apropos Papeete, the capital of Tahiti, in one of the book’s many Lonely Planet-style passages. “[In buying one] be sure to look for a certificate of authenticity on the wall of a shop... Best advice: Shop around.” That’s good to know. Alas, he learn rather less about the lives of local Jews.

During his visit to St. Petersburg, Frank tells us more about Jews who lie underground, in a local cemetery, than those above it. “One always meets ‘ghosts of the past’ in Russia,” he notes. Be that as it may, the reader may also yearn to meet a few living souls.

In Moscow, the author writes, “I visited Jewish day schools, met with college students, and recorded the rising of new Jewish community and cultural centers.” But he leaves it at that without further detail. In Irkutsk, Siberia, Frank visits a community center where he sees elderly Jewish veterans of the “Great Patriotic War” (as WWII is known to Russians), their jackets bedecked with their wartime medals. If they have fine tales to tell, we never learn what they are.

Soon, all hope has evaporated that we’ll come across some flesh-and-blood local Jews beyond mostly throwaway asides that hint at their existence. Here and there, we do alight on telling details. The floor of the Main Synagogue in Odessa, a city that Russian Jewish greats from Isaac Babel to Haim Nachman Bialik once called home, still bears the lines of a Soviet-era basketball court.

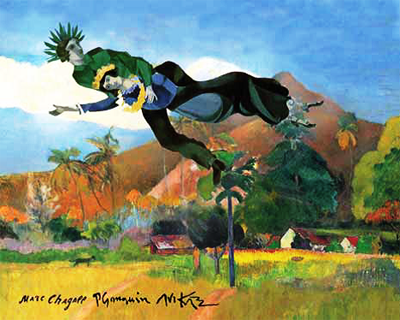

In Papeete, the 200 or so Jewish residents – who have organized themselves into the Cultural Association of Israelites and Polynesian Friends – can boast of living in “the farthest place on Earth from Jerusalem, the exact antipode,” Frank writes, quoting a magazine article. The congregation is also the last on Earth to begin and end every Shabbat, which its French-speaking Orthodox Jewish members do without a resident rabbi. “Paradise is only in Jerusalem,” Mrs. Joseph Sebbag, a prominent local Jew, tells the visiting writer wistfully.

The community of pearl traders, Frank reports, traces its origins to the adventurer Alexander Salmon (nee Solomon), the scion of a British Jewish banking family who arrived on the island at age 19 in 1841. He went on to wed Princess Arrioehau, earning himself the epithet Arii Taimai (“Prince from the Sea”), and to rule Easter Island for a decade after 1878. One of Salmon’s daughters would become the last queen of Tahiti before the island officially became a French colony in 1880.

Frank is a proud Jew with a restless curiosity about “my people” in far-flung places. His love of things Jewish suffuses The Scattered Tribe. Yet with its curious mishmash of vignettes about his various ports of call – some informative, some bland, many of them only tangentially related to local Jews – the book often reads like a collection of a casual traveler’s diary entries. It may not have helped matters that almost everywhere Frank went, he apparently did so on guided tours.