Untold Secrets

A new book claims that Harry Houdini’s real life was even more secretive and mysterious than his public image

Tibor Krausz

The Jerusalem Report, February 5, 2007

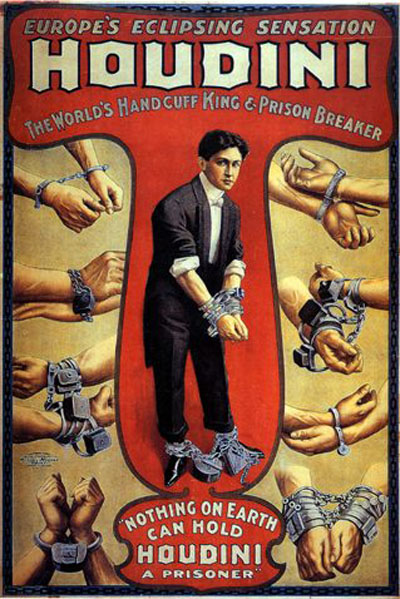

Houdini. The name conjures up instant associations: Grand Master of Illusions, escapologist extraordinaire, implacable bane of occultists. Eighty years after his death, Harry Houdini remains a household name, even though not many of us can describe a single trademark trick of his.

His biographies, biopics and internet tribute sites abound, yet do we know who he really was? Not according to William Kalush and Larry Sloman. In their biography, Kalush, a professional magician, and Sloman, a writer, attempt to reveal Houdini's unknown persona. Their magnum opus (592 tightly written pages without references, which are available separately on a website) is the result, they say, of two years spent scouring archive after archive, including all 17,000 pages of Houdini's scrapbooks and thousands of his letters.

No, they posit, Houdini didn't die (on October 31, 1926) from appendicitis (much less on stage during a failed escape, as an urban legend has it); he was murdered. Then Kalush and Sloman go one better and argue that in his life too there was far more to the Master Illusionist than met the eye. They speculate that Houdini was a secret agent working for the fledgling U.S. Secret Service. Espionage then was still a gentlemen's game, and under the cover of accepting escape challenges Houdini could easily case German munitions factories.

It's intriguing stuff. Yet the theory suffers from a sorry dearth of detail about Houdini's alleged spying career. Thus, "The Secret Life," though comprehensive, fails to live up to its own billing: if the master magician did have a secret life, little of it emerges from the book. Houdini's amazing stunts are minutely detailed, but if hundreds of pages' worth of vignettes listing them (often relayed in chronological disarray, making for a disjointed, episodic read) add up to a true expose, this reviewer must have missed it. Meanwhile, it emerges only bit by bit (from some of Houdini's diary entries quoted seemingly at random) that the plucky daredevil was a henpecked husband tormented by the violent mood swings of his diminutive wife.

Largely lost is the man behind the legend: an audacious Jewish immigrant of short stature, earthy good looks and magnetic personality who defied his lowly origins and conquered the world of vaudeville through grit and hard work. We care about superheroes, like Superman or Spider-Man, only because we know the failings and foibles of their ordinary alter egos, Clark Kent and Peter Parker. Kalush and Sloman tell us plenty enough about Harry Houdini the escapologist superman, but rather less about Ehrich Weiss the common man. Now and again, he does shine through in throwaway anecdotes, such as when he asks his entire salary for high-profile performances in New York in gold coins so he can shower his beloved mother in gold.

Descriptions of his persistent stage fright also help humanize him. As he escaped from ever greater challenges (from inside a hot-water boiler, a crazy crib, a man-size milk can, the famous "Chinese Water Torture Cell") to ever greater fame, Houdini was wrecked by mounting anxiety that perhaps the next test would finally best him. "All the time I was in there, I was thinking of death," he's quoted recalling after he sweated his way out of shackles while locked inside a coffin. The magician also jealously guarded his stranglehold on escapology, ruthlessly exposing and discrediting upstart imitators. "I'm a Magyar and Magyars are vain," he remarked.

Then here's Houdini explaining, in a contemporary interview, about his willingness to mortify himself for ever newer feats: "I strain and sob and exhaust myself, and begin again, and exhaust myself again [but] a man is only a man and flesh revenges itself... Now I'm old at 36."

* * *

Harry Houdini was born in 1874 in Budapest, Hungary, as Erik Weisz, the third of six children fathered by Rabbi Mayer Samuel Weisz, a soapmaker by trade, who emigrated with his family to Appleton, Wisconsin, when Erik (now called Ehrich Weiss) was four. Three years later, after a visit to a traveling circus, where he was enthralled by a trapeze artist, young Ehrich fastened a rope between two trees and started tightrope walking. The athletic boy debuted in show business aged 9 on October 28, 1883, in the sandlot of an enterprising local teenager's 5-Cent Circus. For his first stunt, Ehrich picked up a pin with his teeth while bending over backwards.

When his father was dismissed as rabbi by Appleton's Jewish community over his "old-fashioned" ways and his family fell on hard times, he made Ehrich swear on the Torah that he'd always look after his mother, Cecilia, whom the son would adore for the rest of his life. The 12-year-old boy did promise and would keep his promise. For the time being, he helped ends meet by working as a courier and apprenticing to a locksmith, under whose tutelage he pried open the keyless handcuffs of an acquitted felon with his lock-pick fashioned from piano wire. An escape artist was born.

By 1892 Harry Houdini (as Erik named himself after his childhood hero Robert-Houdin, a French magician) and his younger brother Theodore were performing 20 illusionist shows a day at a downtown museum. Soon Harry perfected an act he called Metamorphosis, a substitution trunk trick wherein a cuffed and bound Houdini "metamorphosed" into his young wife and assistant, Beatrice. He performed it two dozen times daily for $12 a week in beer halls, dime museums, even bordellos. (During his career Houdini would perform the trick over 11,000 times.)

A relentless innovator, the itinerant magician devised one escape stunt after another challenging police officers and craftsmen alike to chain and lock him up so he couldn't escape. No devilish combination of cuffs, ropes, or leg irons could detain "The King of Handcuffs," who wriggled out of them faster than it took to shackle and bind him (he got out of a straitjacket in a minute even while hanging upside down). If he needed to cut and bruise himself in the process, so be it. Mystified by his seemingly supernatural bravura, some people suggested Houdini, who carried with him a miniaturized set of the Ten Commandments as a charm, had learned the secrets of Kabbalah from his scholarly father, mastering the arcane mysteries of dematerialization. Houdini himself explained: "[I]t's chiefly through my ability to twist my body and dislocate my joints [that] renders me independent of the tightest bonds."

A brazen self-promoter, Houdini became only the 25th man to pilot a powered proto-airplane and went down in history in 1909 as the first aviator to fly in Australia after lifting up successfully in a rickety deathtrap. No less than such death-defying stunts, it was Houdini's showmanship and painstakingly choreographed dramatization that would immortalize his name. By the 1910s, the son of the poor Hungarian rabbi had become an international vaudeville superstar, earning $400 a week — the equivalent of $45,000 in today's money. He was the American Dream personified.

* * *

Like many a magician, Houdini had it in for mediums. Deception was his stock in trade so he could spot humbuggery when he saw it. Yet he claimed to remain open-minded about Spiritualism, a pseudo-religion all the rage at the time with its table rappings and outpourings of ectoplasm. The death of his mother in 1913 left Houdini disconsolate, waking up at night and shouting, "Mother, are you there?" Nine years later, during a séance overseen by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of Sherlock Holmes and an ardent Spiritualist, his mother contacted Houdini through Lady Doyle, a medium. Except that the late Jewish woman drew the sign of the cross and held forth in perfect English, not in Hungarian, Yiddish or German, the languages she could actually speak while alive.

Refashioning himself a psychic investigator, Houdini went on a crusade against fraudulent mediums, orchestrating sting operations by his army of undercover agents (one of whom brazenly used the alias F. Raud, for "fraud") who infiltrated Spiritualists' covens. Houdini exposed the machinations of occultists in his bestsellers "Miracle Mongers and Their Methods" and "A Magician Among the Spirits," and incorporated the debunking of mediums into his stage repertoire. "I have never seen a mystery I could not fully explain," noted the man, who years earlier had mystified Theodore Roosevelt during a simulated séance by answering the president's secret question as if by supernatural means, before confessing: "It was hocus-pocus." The rabbi's son never denied the possibility of an afterlife, but maintained that faking tipping tables and gooey ectoplasm as manifestations of the supernatural was an insult to "the ineffable majesty of the Almighty."

It's here, in its third part, that the book comes alive. In a gripping, tongue-in-cheek narrative, Kalush and Sloman document Houdini's quest to debunk mediums in "the greatest humanitarian achievement of my life," as he said. As occultists cultivate the same type of ambiguity magicians employ, namely that anything extraordinary seems to have supernatural causes, Houdini understood that our boundless capacity for "miracles" makes us sitting ducks for unscrupulous con artists who exploit our deepest hopes and fears.

Meanwhile, Spiritualists were praying fervently for his death. They got their wish on Halloween in 1926, when, having come down with excruciating abdominal pains during a show in Detroit three days previously, Houdini died in hospital. The diagnosis was appendicitis, but Kalush and Sloman theorize that the great illusionist-debunker was murdered by an agent of his Spiritualist enemies who, under the ruse of testing the magician's rock-solid stomach muscles, delivered fatal blows to his lower abdomen. The blows are well-documented; the Spiritualist angle isn't. Still, the Houdini mystique will hardly suffer from some further mystery.

Houdini believed if anyone could escape from the afterlife, it was he. Before his death, he left a secret code to his wife, Bess (who, labeling herself "your shekinah," would attend countless séances), for proof positive that his soul did indeed return from the dead. To date, the spirit of Houdini hasn't credibly been heard from. It's a pity, for I'd sure love to meet him.